FAIRR’s recent regenerative agriculture report found that 63% of the world’s largest 79 listed agri-foods businesses discuss the farming system, shedding light on how corporations view this shift as an opportunity to address the climate, nature, and social impacts of their supply chains. Yet such initiatives have so far focused on soils and terrestrial agriculture, leaving the environmental benefits and investment opportunities in aquatic systems, such as aquaculture, untapped. Regenerative aquaculture, sometimes referred to as restorative, aims to deliver commercially viable products with ecological benefits, resulting in net positive environmental outcomes. Crucial in this transformative process is the integration of seaweed.

So, Why the Excitement Around Seaweed?

The world of seaweed is remarkably diverse, boasting over 12,000 known species. Only 0.1% of these species are used commercially but these already deliver a myriad of applications, as illustrated in Figure 1. In addition to its vast diversity, seaweed's appeal is amplified by its positive contribution to ecosystems. Macroalgae plays a pivotal role in supporting biodiversity, carbon sequestration, and bioremediation. These are essential to combat pressing global challenges such as eutrophication, ocean acidification, and climate change.

Seaweed cultivation is inherently regenerative, though, there is a need to deepen knowledge on this at scale. Unlike traditional terrestrial agriculture, seaweed farming doesn't require fertilisers, pesticides, freshwater, or extensive land. With the rapid growth of the aquaculture industry and ample ocean space there is a clear potential for seaweed in enabling economic diversification and environmental remediation in coastal and offshore marine environments. Ocean Forest (supported by Leroy and Bellona Norway) is a leading example of such a system, cultivating seaweed within salmon aquaculture having determined its economic and environmental potential in function, increasing resource efficiency and reducing pollution, and as a product.

Figure 1: Various applications of seaweed.

Source: Seaweed for Europe

Asia Dominates Global Seaweed Production

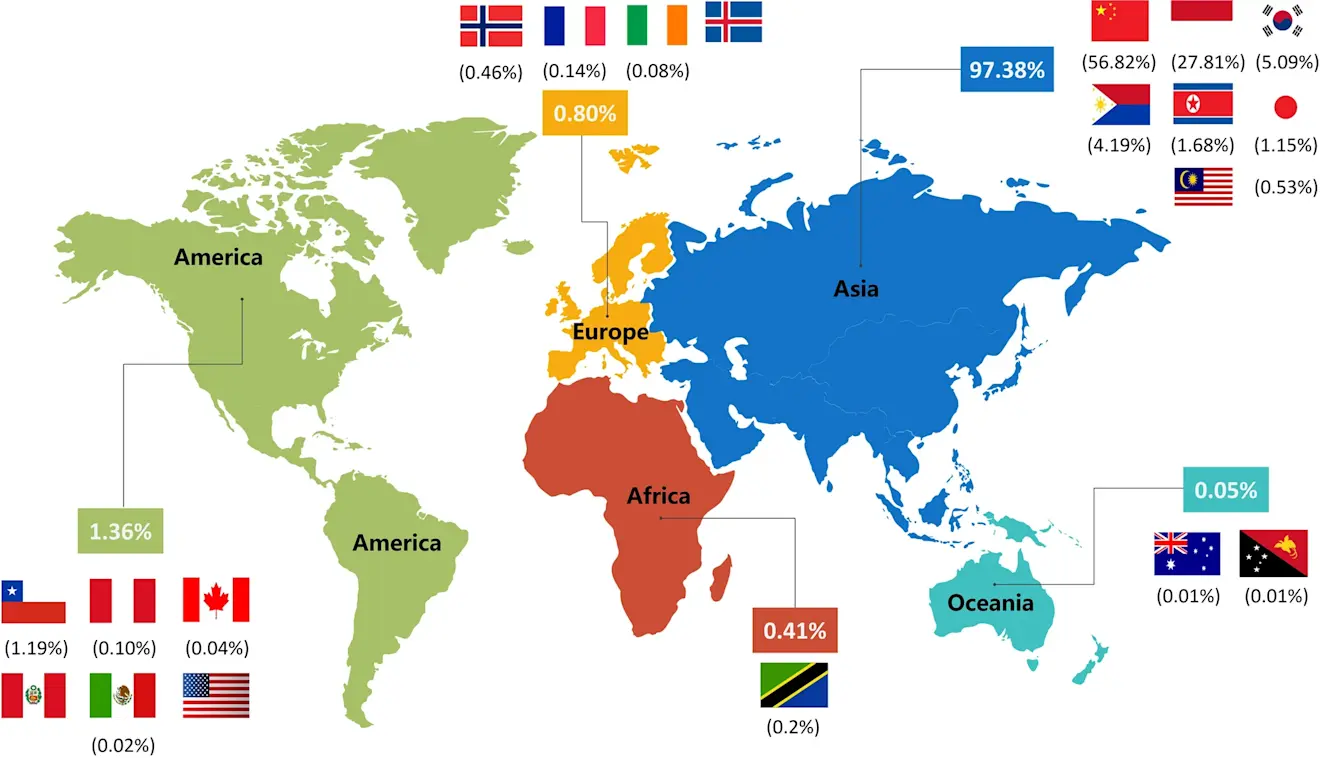

From 2015 to 2020, the FAO estimated that seaweed production accounted for 29% of global aquaculture (excluding shells and pearls) at 35.1 million tonnes live weight, growing at an annual average rate of 2.5%. Of this, cultivation makes up over 97% of production, with wild harvest making up the remaining 3%. Asia, specifically countries like China, Indonesia, South Korea, and the Philippines, are responsible for the majority of global production (see figure 2). Seaweed has traditionally been a dietary staple in Asia, providing consumers with nutrients and antioxidants. This, along with a high demand for carrageenan and agar (food additives and gelling agents extracted from seaweed) and a climate supporting multiple harvest cycles resulting in high annual yields, has fostered a robust supply and demand relationship. In contrast, such a strong dynamic in Europe and the Americas is yet to develop.

Figure 2: Global production rates of seaweed.

Source: Food Production, Processing and Nutrition

Opportunities and Barriers in Europe and the Americas

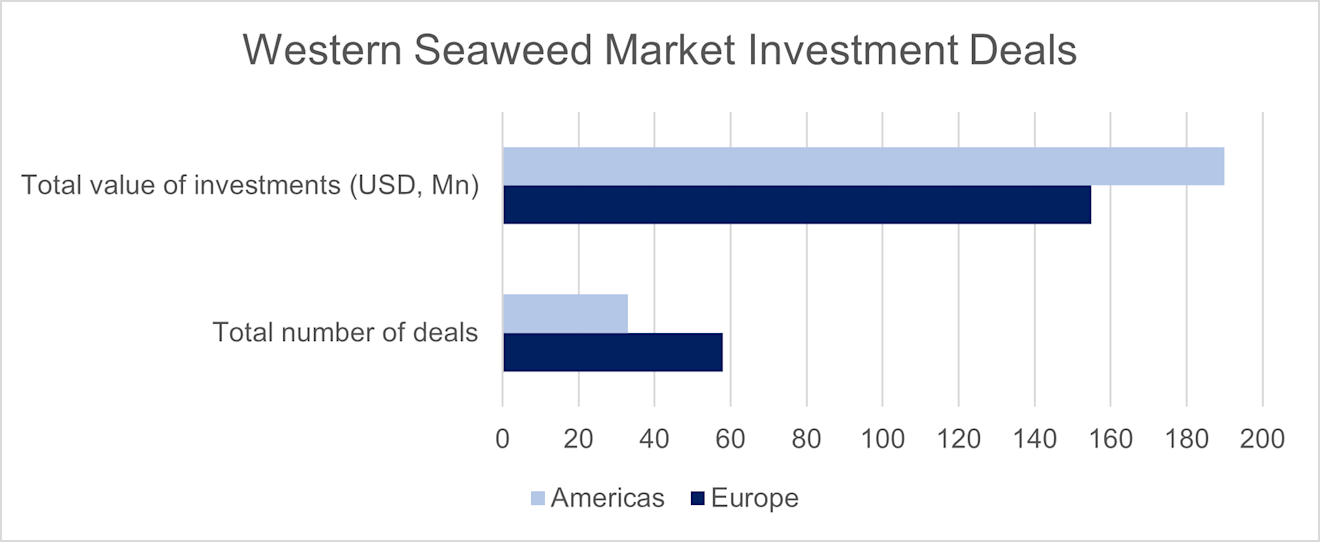

Figure 3: Total number of investment deals and their value between 1 January 2020 and 1 January 2023.

Source: Phyconomy Database

Seaweed aquaculture in Europe and the Americas is currently spearheaded by Chile, Maine, Alaska, France, and Norway – though the rate of expansion is far from that observed in Asia. Private investment and early stage funding, as illustrated in figure 3, amounts to approximately $190 million across 33 deals in the Americas and about $155 million across 58 deals in Europe. While this appears positive, the figures are dwarfed by the Salmon industry – Bakkafrost alone plan to invest $886 million in farming Scottish salmon between 2022 and 2026. Nevertheless, these markets are increasingly recognising the potential of seaweed – estimates from the European Commission indicate the European seaweed market may reach $9.5 billion by 2030, generating approximately 85,000 jobs. This optimistic outlook underscores the growing interest and efforts to tap into the vast possibilities offered by seaweed aquaculture in the Western world.

Typically, seaweed production in colder waters is highly seasonal, producing a single harvest annually between April and May. Managing large annual volumes of seaweed incurs costs associated with the equipment necessary for automation in harvesting and drying. This contrasts with other fish and seafood productions where assets are used more consistently, raising their return on investment compared with seaweed. The result is high retail prices for seaweed products in Europe and North America, reducing consumer demand and creating a negative feedback loop by limiting the financial appeal of scaling up production. The relative lack of investment in seaweed in those regions also slows the resolution of such bottleneck issues. Addressing these processing and logistical challenges is pivotal to unlock growth in these markets.

The Role of Investors in Europe and the Americas

In the European and American markets, current investment predominantly focuses on product development which draws venture capital due to the promising returns. However, this approach might not be the most conducive to industry growth. The bottleneck issues lead potential users of seaweed in sectors like bioplastics, pharmaceuticals, and nutraceuticals (functional foods), to seek a steadier supply of raw ingredients from Asia. As a resolution, blended finance, and impact investors present viable avenues for raising the capital efficiency of seaweed cultivation and processing. Such advances in production could drive down final product costs and secure the regenerative benefits of seaweed farming.

One such mechanism for unlocking these benefits is scaling investment into biorefineries – an innovative approach that offers the potential for an economically feasible process deriving multiple products from a single input of seaweed. If located near cultivation sources, refineries maximise the efficiency of macroalgal production by limiting energy costs when transporting wet mass seaweed along with creating both high and low-value products for diverse markets. Furthermore, through storage and preservation alongside a diversified product range, refineries have capacity to produce outside of peak season, thereby promoting sustainable industry growth.

The development of carbon and biodiversity markets in the blue economy may also help improve the financial viability of seaweed farming. Challenges remain around establishing their credibility along with transparency across the value chain – yet, down the line these could significantly contribute to the growth of the seaweed industry. Hand in hand with this is a need for developments in regulatory support to address biosecurity and genetic challenges – an area that organisations such as the FAO and Safe Seaweed Coalition are beginning to pave the way for. By facilitating cultivators and releasing the bottle neck in supply there are considerable opportunities for regeneration and value in Western seaweed markets.

FAIRR insights are written by FAIRR team members and occasionally co-authored with guest contributors. The authors write in their individual capacity and do not necessarily represent the FAIRR view.