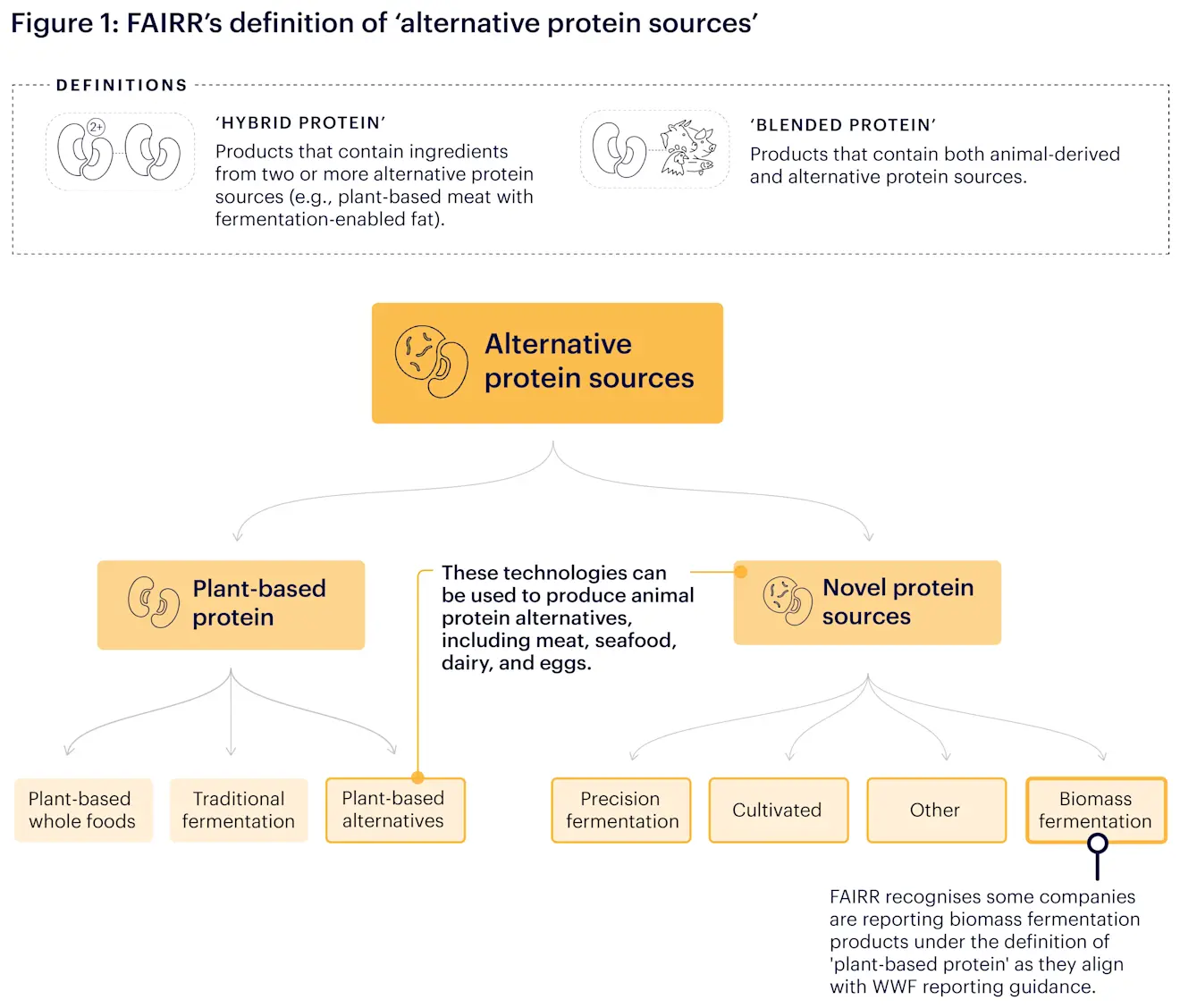

The overconsumption of animal proteins in high-income countries disproportionately contributes to climate change, degrades natural ecosystems, and is linked to increased incidences of non-communicable diseases (NCDs). With the demand for animal protein growing in parallel with population growth, there is a need to transition away from excess animal protein consumption if we are to feed the planet in a resource-constrained world. Greater consumption of alternative protein sources (Figure 1), including plant-based whole food proteins and novel protein sources, is key to mitigating public health, climate, and nature-related risks and achieving long-term food security. Companies, investors, and governments will play a crucial role in accelerating and maximising the adoption of diverse protein sources that support healthy and sustainable diets.

The Hidden Costs of Industrial Animal Protein Production

Since the 1920s, in many countries animal protein production has undergone a significant transformation away from a predominantly pastoral family-owned farming system to a highly concentrated and industrialised system of production, increasing the availability and accessibility to cheap meat. However, 100 years later we continue to unravel how the reliance on industrialised animal agriculture comes at a cost to the wider economy. For example, in 2019 the beef industry in Brazil (including retail and associated sectors) despite contributing to 8.5% of the country’s GDP was linked to 90% of deforestation in the Amazon. This in turn caused losses to the domestic economy of over US $285 billion, which was equivalent to 15% of the country’s GDP that year.

At a global scale, estimates suggest that the global food system's hidden costs of natural capital, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, pollution, pesticides, obesity and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) were USD $8 trillion in 2018 - equivalent to 9% of global GDP that year. These costs are expected to increase to USD $13 trillion by 2050 if no action is taken and could be further compounded by the sector’s vulnerability to the negative feedback loops resulting from its impact on the environment and public health (Table 1).

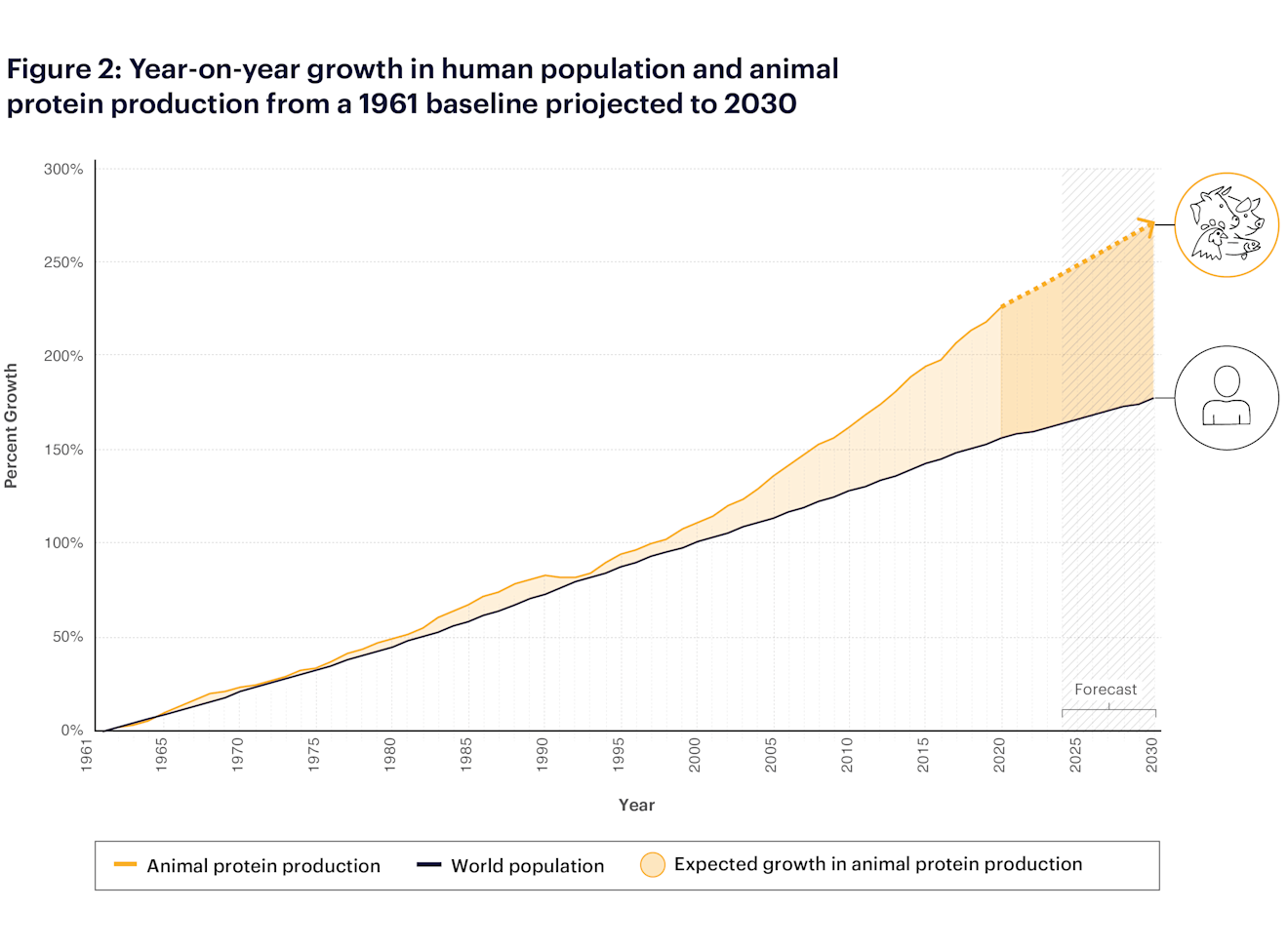

With the global population expected to reach 8.5 billion by 2030, an 8% increase from 2020, and with incomes on the rise, animal protein production is projected to grow by 14% in the same period (Figure 2). To prevent the impacts of industrial animal agriculture from escalating further, production and consumption patterns need to be more sustainable. While integrating practices such as regenerative agriculture, increasing nutrient efficiency, and improving on-farm energy use have significant climate mitigation potential these efforts alone are insufficient. There is a need to reduce excess demand for animal proteins, particularly in the West and shift diets towards more plant-based sources to ensure the food system can meet the world's growing demand for protein.

Source: FAIRR analysis based on FAO stat data via OurWorldinData for the production meat & milk, seafood, eggs, UN World Population Prospect data, and OECD

Addressing Climate, Nature and Public Health Impacts through Sustainable and Healthy Diets

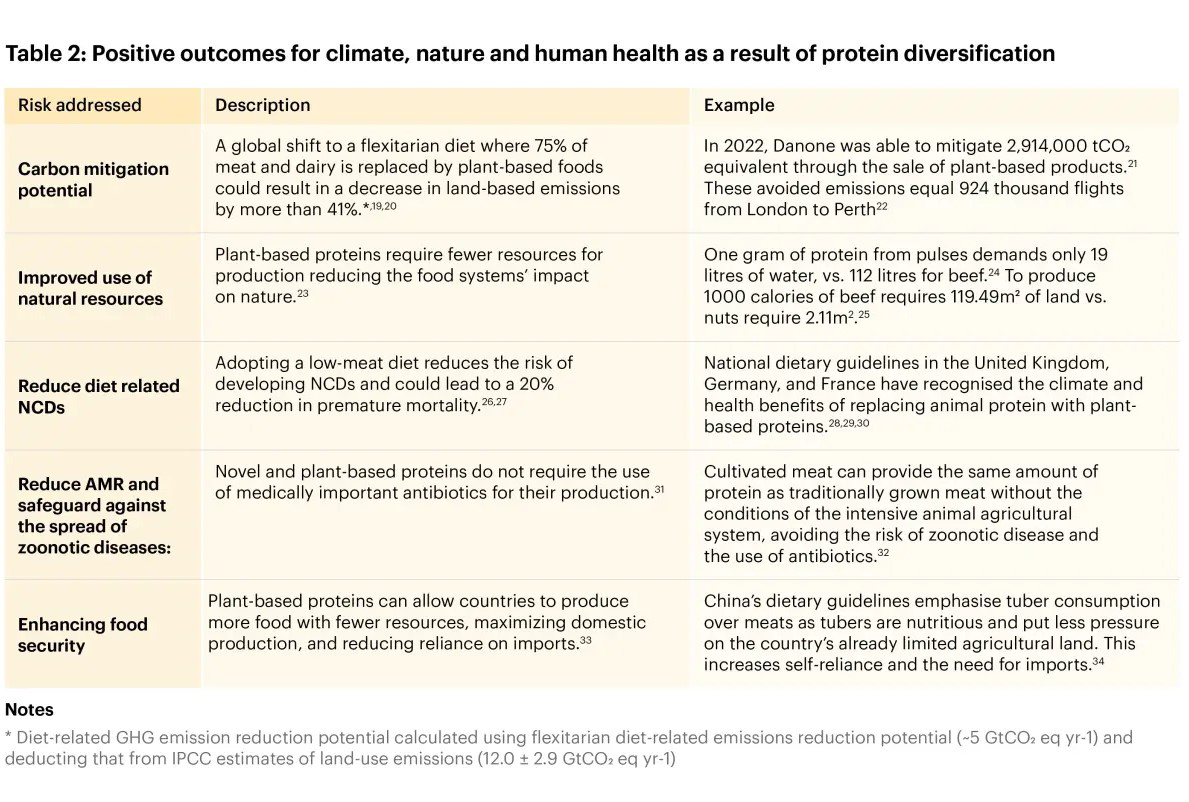

Plant-based wholefood proteins, such as legumes, pulses, nuts, and seeds can satisfy a growing demand for protein while avoiding many of the negative externalities and material risks of the industrial animal agriculture system (Table 2). The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) and the World Health Organisation (WHO) have identified the intrinsic link between replacing the excess consumption of animal protein with plant-based foods and positive outcomes for climate, nature and human health.

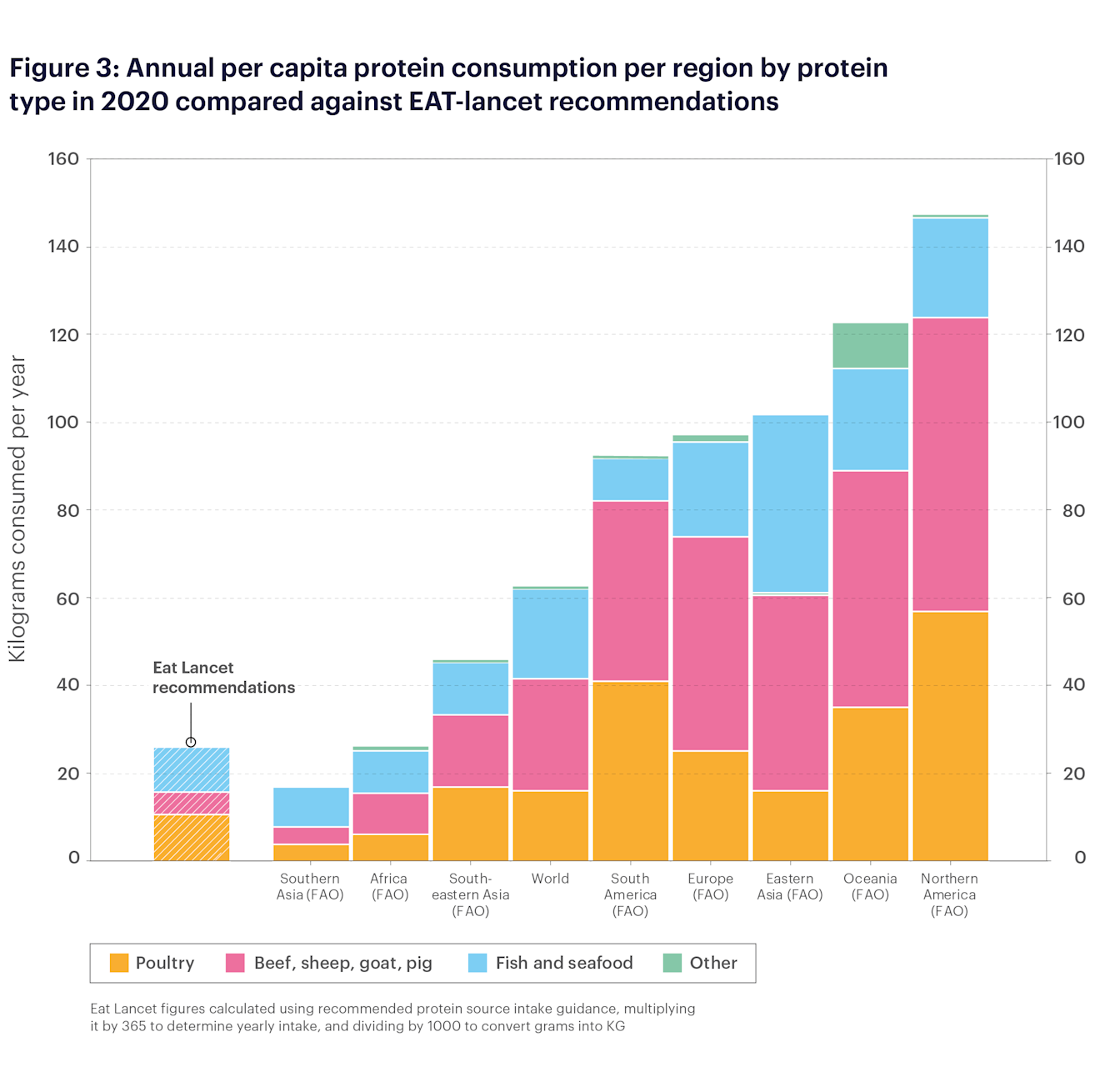

The Eat Lancet’s “Planetary Health Diet” proposes that animal protein intake should be limited to 84 grams a day (excluding dairy products) and at least 125 grams of plant-based proteins be consumed daily. Achieving a global adoption of the Planetary Health Diet requires doubling the consumption of nutrient-rich foods like fruits, vegetables, legumes, and nuts while halving the intake of less beneficial options such as added sugars and red meat.

Manufacturers and retailers are increasingly recognising the interconnectedness of protein diversification in achieving climate, nature, and health goals. Companies such as Ahold Delhaize, Danone, Nestle, Sainsbury's, and Tesco are beginning to update their strategies to reflect that sustainable healthy diets are those rich in plant-based foods. However, many companies have yet to realise the associated benefits of integrating protein diversification into relevant corporate strategies (i.e. promoting healthy diets and reducing scope 3 emissions).

Efforts to diversify protein product portfolios are frequently limited to ‘healthy’ or ‘vegetarian’ brands or product ranges and leave out those most exposed to animal proteins. This approach is also evident in how companies engage consumers through marketing and promotions. There is a concerted need to better equip consumers with the knowledge to make choices that are better for their health and the environment.

Meat, Seafood, and Dairy Alternatives: Aids in the Protein Transition

While plant-based wholefood protein sources like legumes and pulses offer a variety of benefits, consumer's willingness to replace their intake of animal proteins with these options is questionable. Innovation on novel protein sources that seek to replicate the taste and texture of animal proteins without the accompanying negative health and environmental impacts is key to supporting a dietary transition.

The meat, seafood and dairy alternative sector was expected to grow at an annual rate (CAGR) of 8% from 2017 to 2021. However, as of 2023 consumer interests in these products has been mixed. Plant-based milks have been received positively and is expected to continue to grow in market size by 15% CAGR from 2023 to 2030. Alternative meats have not seen the same success. In 2023, UK plant-based meats fell to £523 million in sales, declining for the second year in a row since 2021. This has prompted companies to pull product lines and reduce capital investment. Reasons for this shift include, firstly, concerns about the health and nutrition of plant-based alternatives, with critics claiming they are ultra-processed or fail to meet the nutritional standards compared to their counterparts. Yet, recent studies challenge these assertions, highlighting that alternatives may have better health outcomes than their processed animal-based equivalents. Second, the price premium paid for these combined with the cost-of-living crisis are deterring consumers from adopting these products. For example, in late 2023 Beyond Meat’s vegan burger UK retail price was £10.22/kg more than Tesco’s premium own-label beef burger which cost GBP £8.81/kg. Finally, companies have struggled to provide products with the taste and texture consumers are looking for, preventing repeat purchases. Overcoming these challenges will be key to ensuring alternatives are adopted by consumers.

Bringing Novel Protein Sources to Market

Novel protein technologies remain largely in their infancy. The cost of growth medium remains high, large-scale bioreactors are limited, and the science behind optimised cell scaffolding is still under development. Nonetheless, there has been a downward trend in production costs. For example, the cost of producing cultivated chicken has dropped by 99.9% since 2013 declining from $280,400/kg to $18 a kg in 2022. While encouraging, efforts must continue to create parity with their traditionally grown counterparts if they are ever to be used to replace their consumption.

Slow-moving, complex, and often confusing regulatory approval processes is a further barrier to the industry. Singapore and California are positive examples where policy support has been able to help drive down the cost and advance novel protein technologies supporting companies bring products to market.

Geographical and Demographic Considerations When Advocating for Protein Diversification

Protein diversification is not a one-size-fits-all approach. Although nutritional requirements vary across countries and demographic groups, the need for balanced protein intake that avoids excess consumption of animal products is key to achieving healthy and sustainable diets. For example, for North America and Oceania, a significant reduction of up to 82% in annual meat consumption is needed to align with the Eat Lancet recommendations (Figure 3). Conversely, in Africa and South Asia, where limited access to a diverse range of foods may hinder the consumption of essential micronutrients, animal protein plays a vital role in preventing malnutrition. Furthermore, vulnerable groups such as pregnant and breastfeeding women, children and the elderly may face challenges obtaining nutrients solely from plant-based sources without fortification. Hence, governments, companies, and key stakeholders must consider protein diversification against local nutritional needs. In some cases, this will require increasing meat consumption up to the EAT-Lancet’s recommendations of 84 grams to help populations fulfil their daily nutritional needs.

Source: FAIRR analysis based on FAO Data via OurWorldinData & EAT-Lancet Commission on Healthy Diets From Sustainable Food Systems

The Protein Transition Must Be a Just Transition

Farmers, workers, and communities dependent on industrial animal agriculture play a pivotal role in driving the long-term sustainability of the agri-food system. Any protein diversification plan at the corporate or national level must consider the implications and seek to mitigate any adverse impacts on their livelihoods to ensure a Just Transition. For example, facilitating training to upskill farmers and access to technical and financial support from public and private entities to leverage emerging opportunities presented by the sector transformation.

Future Outlook for Protein Diversification

With animal protein production and consumption expected to grow, there is a need to diversify protein sources we eat to promote diets that are both healthy and sustainable. Transitioning to healthy and sustainable diets requires a coordinated approach from policy makers, investors and large-scale corporates. FAIRR proposes the following recommendations for each of these stakeholders who have a key role in the protein transitions:

Policymakers

Update dietary guidelines to recommend a plant-rich diet, and reduced animal protein consumption. These guidelines should be mindful of the cultural and nutritional needs of national populations.

Utilise public procurement to increase plant-based eating in alignment with updated dietary guidelines.

Redirect subsidies to support the production of alternative protein sources.

Further clarity and streamline of approval processes for novel protein companies attempting to bring innovations to market.

Implement policies that safeguard stakeholders that may be negatively impacted by a global shift to a more plant-based diet, developing policies through consultation and engagement with these stakeholders.

Investors

Engage with portfolio companies to ensure they are including protein diversification in their climate transition plans.

Allocate financial flows to address the key roadblocks for scaling the production of alternative protein sources. For example, invest in increasing the availability of bioreactors, decreasing the cost of the growth medium, and advancing research into optimised cell scaffolding.

Large-cap companies

Integrate protein diversification into climate transition plans, ensuring this integration also aligns with public health outcomes.

Ensure that the principles of Just Transition are followed when diversifying the company's protein portfolio.

Allocate resources to expand the company’s portfolio of alternative protein sources beyond plant-based focused brands and formulate products to have positive sustainability and nutrition attributes.

Implement marketing interventions that promote the adoption of an increased consumption of plant-based proteins.

References

2 https://www.fao.org/3/cb7514en/cb7514en.pdf

3 https://www.fairr.org/tools/climate-risk-tool#tool

4 https://ourworldindata.org/what-are-drivers-deforestation

5 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305750X21001972

6 https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1029/2019WR026995

12 https://amr-review.org/sites/default/files/160525_Final%20paper_with%20cover.pdf

13 https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/323311493396993758/pdf/final-report.pdf

14 https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1208059110

15 https://bulletin.woah.org/?panorama=02-2-2-2020-1-economic

16 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2697260/

17 https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12916-023-03093-1

18 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10617206/

19 https://www.ipcc.ch/srccl/chapter/summary-for-policymakers/

21 Danone 2022 CDP Climate Report

24 https://chembioagro.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40538-016-0085-1

25 https://ourworldindata.org/land-use-diets

26 https://www.fao.org/3/ca6640en/ca6640en.pdf

27 https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12916-023-03093-1

28 https://www.dge.de/gesunde-ernaehrung/dge-ernaehrungsempfehlungen/10-regeln/

29 https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/eat-well/food-guidelines-and-food-labels/the-eatwell-guide/

31 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10389608/

32 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10389608/

33 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S092422441300109X

FAIRR insights are written by FAIRR team members and occasionally co-authored with guest contributors. The authors write in their individual capacity and do not necessarily represent the FAIRR view.