Introduction

The Paris Agreement is an international treaty on climate change, adopted by 196 Parties at COP 21 in Paris, December 2015, that entered into force in November 2016. Governments have committed under Article 2.1c of the Paris Agreement to “making finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development”. This has implications for financial stakeholders and investors in the agriculture and food sector, as we will explore in this paper.

The agriculture and food sector is particularly vulnerable to climate change, but it also harnesses the potential to contribute to climate change mitigation. Studies have found that natural climate solutions can provide over one-third (37%) of the cost-effective climate mitigation needed between now and 2030 to stabilise warming to below 2°C. However, a large portion of reforestation mitigation potential depends on production efficiency or dietary shifts to reduce beef consumption2. Another recent study found that shifts in global food production to plant-based diets by 2050 could lead to sequestration of 332–547 GtCO2 as land could be made available for ecosystem restoration, equivalent to 99–163% of the carbon budget. This is consistent with a 66% chance of limiting warming to 1.5 °C, approximately 9–16 years of global fossil fuel emissions.

What is Article 2.1c of the Paris Agreement?

Governments have committed under Article 2.1c of the Paris Agreement to “making finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development”.

Under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), governments have now established a ‘Standing Committee on Finance’ to assist functions concerning the Financial Mechanism of the Convention and to serve the Paris Agreement. According to an analysis by the Standing Committee on Finance, governments and private sector investors have been scaling up finance to address climate change. Climate finance flows increased by 17% in 2015–2016 compared to 2013–2014, and the high-bound global climate finance estimates increasing from $584 billion in 2014 to $681 billion in 2016, on a comparable basis, largely made up of investments into renewable energy. Whilst data on the energy transition is more widely available, high-quality data on private investments towards climate change in other sectors such as agriculture is currently missing. However, the quality of data has been improving. The next report will aim to look more closely at the consistency of finance flows according to Article 2.1c of the Paris Agreement. The enhanced transparency framework under the Paris Agreement also has relevance for agricultural finance flows, as it includes provisions for better data disclosure, including on areas such as deforestation.

This policy paper aims to summarise the state of play regarding the implementation of the finance goal of the Paris Climate Agreement (known as ‘Article 2.1c’) in the agriculture sector. In terms of public finance flows to agriculture, the paper will summarise available data and research with a particular focus on subsidies and taxation before covering existing work under the PRI’s Inevitable Policy Response. This includes the likely future policy responses in the agriculture and food sector and emerging topics under consideration by policymakers, such as a potential ‘livestock levy’. The alignment of public finance flows with climate goals also has implications for investors, companies and farmers. In terms of private finance flows to agriculture, the paper will explain how actions and coalitions led by other private actors, including investors, banks, and corporates, contribute to alignment. FAIRR’s own research contributes to this by providing data to investors on the climate and deforestation risks at major protein producers and enabling investors to conduct climate stress testing of their portfolio.

Aligning Public Agricultural Finance Flows with the Paris Climate Goals

Climate change has implications for companies, producers, and farmers in the agriculture and food sector in terms of direct and indirect physical risks and transition and liability risks. Notably, 14.5% of anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions come from livestock supply chains, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Furthermore, 70–80% of all global agricultural land is used for pasture and growing crops for animal feed. Animal agriculture systems will suffer increased water, feed, and infrastructure damage due to extreme weather events. These costs are already being felt. Climate change has reduced Australian farms’ average annual profitability by 22% over the last 20 years.

There is a range of mechanisms and policy levers through which governments and regulators may align public finance with the Paris climate goals and affect the flows of private finance to agriculture. According to Whitley et al. (2018), this toolkit includes financial policies and regulations, fiscal policy levers, public finance and information instruments. For this policy paper, we will focus on fiscal policy levers (with a focus on subsidies and taxation) and financial policies and explore the implications of the integration of agriculture into other climate change policy levers. However, whilst the scope of this policy paper is limited, further work could potentially focus on analysing other policy instruments such as information instruments.

Subsidies

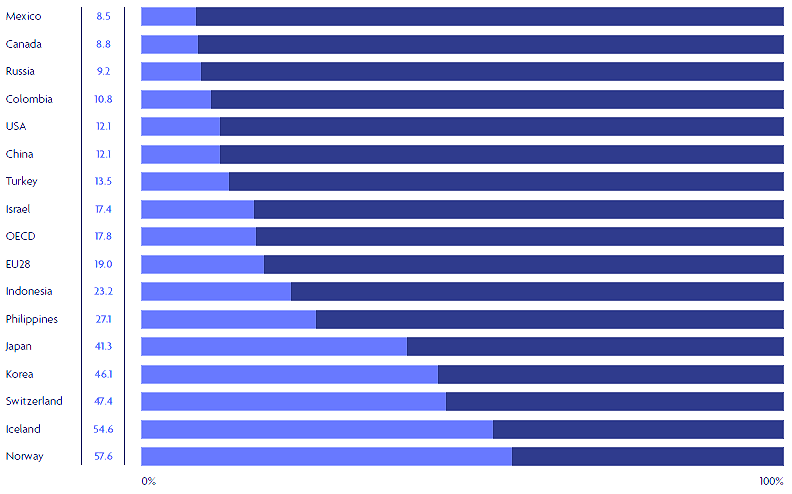

In many countries, current agricultural production is supported by public funding. According to the OECD (Fig. 1), support for agriculture made up 18% of total farm receipts in OECD countries in 2019.

There is a range of agricultural subsidies that go towards high-emitting agricultural systems, including industrial livestock farming in terms of subsidies. These subsidies may be reformed in the coming decades under efforts to align public finance with the goals of the Paris Climate Agreement. At a global level, research by the World Bank shows that countries that produce two-thirds of the world’s agricultural output provided $600 billion per year in agricultural financial support on average from 2014 to 2016. However, the research found that only a modest portion of programmes support environmental objectives and even fewer support climate change mitigation. Of the $300 billion in direct spending, for example, only 9% explicitly supports conservation. Notably, rice, maize, pig meat, beef and veal, and milk products account for roughly three-quarters of total commodity transfers from a product perspective. Reviews of the literature have found that support coupled to production or input use and support in countries with high emission intensities is particularly harmful to the environment. Similarly, on biodiversity loss, the Paulson Institute estimated that government subsidies harmful to biodiversity outweigh the current positive biodiversity finance flows for biodiversity by at least a factor of four. They argue that the global biodiversity conservation gap will not be closed unless there are significant efforts to reform harmful subsidies.

Research suggests that current EU agricultural subsidies are not aligned with climate or biodiversity objectives. Research by the NGO Greenpeace has highlighted that in the EU, between €28.5 and €32.6 billion goes towards livestock farms or producing fodder for livestock. This amounts to 69-79% of CAP direct payments – amounting to between 18% and 20% of the EU’s total annual budget. Environmental advocates have, therefore, called on the EU to reform the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) to align with other EU objectives, such as the ‘Green Deal’, and analysis has been conducted by the European Commission on the linkages between the CAP reform and Green Deal, including the Farm to Fork Strategy. Similar inconsistencies currently exist in other jurisdictions. According to one analysis from 2013, US taxpayers spent $38 billion per year subsidising meat and dairy in the US, with less than 1% of that being spent on fruits and vegetables. As noted in the section below, these subsidies have price impacts by potentially hindering efforts to incorporate externalities into the pricing of agricultural products. The Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition (2020) found that repurposing global agricultural subsidies would lead to reductions in GHG emissions from agricultural production, whilst diets and health would also be positively impacted, with an estimated 600,000 fewer diet-related deaths per year and an increase in consumption of nutrient-rich foods.

Regarding international multilateral and bilateral flows of public finance to agriculture in developing countries, it is notable that agriculture is a small fraction of the total flows of multilateral climate finance. In 2019, around 4% ($1.7 billion) of the mitigation finance from the multilateral development banks (MDBs) went to the agriculture, aquaculture, forestry and land-use sector. However, research has recently found that the International Finance Corporation (IFC) and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) alone provided $2.6 billion for pig, poultry and beef farming, and dairy and meat processing in the past 10 years. The climate change emergency, along with deforestation, biodiversity and health impacts, may mean that public institutions face future calls to phase out subsidies to intensive livestock production and instead, realign lending with lower-carbon agricultural production. Such efforts to reform subsidies will have to consider the need to transition rural livelihoods to more sustainable production and build stakeholder coalitions to support reforms.

Taxation and Pricing

In terms of taxation and pricing, the agricultural sector is being gradually integrated into carbon pricing and emission reduction schemes. Research by the FAIRR Initiative indicates that discussions on a ‘meat tax’ increasingly enter political rhetoric. In November 2019, Dutch Finance Minister, Menno Snel, committed to a study into ‘fair meat prices’ in preparation for fiscal reforms in 2021. The announcement came after the TAPP (True Animal Protein Price) Coalition presented research in the Dutch parliament. In addition, there is mounting evidence associating high meat consumption with a number of health risks. Research by Oxford University found that a ‘health tax’ on red and processed meat could “prevent more than 220,000 deaths and save over $40 billion in healthcare costs every year”.

In addition, the agriculture sector is due to be incorporated into emission trading schemes. New Zealand is set to become the first nation in the world to include agriculture in an emissions pricing scheme, with an emissions pricing system being applied to livestock emissions at a farm level from 2025.

As noted in the previous section, agricultural subsidies to high-carbon foods remain. This may alter the retail price of these commodities in contrast to a level of pricing that would reflect the market and environmental costs. In the US, the average retail price of a burger would be more than doubled by including the hidden expenses of health care, subsidies, and environmental losses. Thus, in contrast to efforts towards carbon pricing, such subsidies can act as a form of negative carbon pricing.

Financial Policies and Regulations

Regarding financial policies and regulations, green finance regulation has been developing over time, and the EU’s Taxonomy Regulation (EU) 2020/852 creates a classification system to help investors more easily recognise “sustainable” products that have implications for agricultural finance. However, it is notable that with regards to the agriculture sector, the side-effects of antibiotic use in the livestock sector are currently not part of the taxonomy criteria, and animal welfare is also not included, although these are recommended in the Annex to be integrated in the future. Trade agreements are also increasingly important for aligning finance flows with the Paris Agreement. This includes forthcoming updates to trade agreements to integrate climate change priorities and leveraging agreements, such as the European Union (EU)-Mercosur Trade Agreement to achieve compliance with the Paris Agreement.

Moreover, mandated climate-related financial disclosure will also have implications for agricultural finance flows. For example, climate-related disclosure by companies in the meat and dairy sector may be lagging behind that of other sectors. In a recent assessment of the world’s largest listed meat companies, as itemised in the Coller FAIRR Protein Producer Index, only two firms (Tyson Foods and Marfrig), or 5% of those assessed, publicly disclosed a climate-related scenario analysis. This was despite the analysis being recommended by the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). By comparison, in the energy sector, 23% of oil and gas, mining and utility companies have undertaken this sort of climate scenario analysis. The integration of climate scenario analysis by central banks and financial supervisors also has implications for the agriculture and food sector. The Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) has noted that agriculture, forestry and land use play an important role in reducing emissions. The scenario for an orderly transition to 2°C shows that the agriculture forestry and land use (AFOLU) sector goes from net positive to net negative CO2 emissions by 2060, with 4Gt of CO2 equivalent set to be absorbed from the atmosphere each year (e.g. by afforestation).

In terms of future implications, food and agriculture are gradually being integrated into general climate change policymaking and target-setting (including carbon pricing schemes). The PRI’s Inevitable Policy Response (IPR) projects that climate policies will fully incorporate land use by 2030, with international payments playing a supporting role in national policies and reducing ruminant meat consumption by 75% by 2050 against the baseline. Furthermore, the longer the delay, the more disorderly, disruptive and abrupt the policy will inevitably be. For example, in the UK, the Committee on Climate Change has recommended that the Government reduce consumption of the most carbon-intensive foods, including reducing beef, lamb, and dairy consumption by at least 20% per person within current healthy eating guidelines. The direct transition risks include expected advances in regulation, including international carbon pricing and markets, the impacts of Paris NDCs, deforestation and biodiversity commitments, and changing consumer preferences. For instance, the Coller FAIRR Climate Risk Tool shows that by 2025, substitution away from cattle toward poultry is expected due to rising beef prices and shifting diets. Indirect risks also threaten protein market valuation, including unsustainable land use and technological/innovation advancements in alternative proteins that will increasingly threaten conventional meat supply chains.