‘Net Zero’ is dominating the climate landscape and the FAIRR Initiative is assessing how companies across the protein supply chain are jumping on this trend, and how sceptical investors should be of the sudden influx of targets. The first blog in this new series will examine what net-zero really means and how it is being translated into commitments by food retailers and manufacturers.

‘Net Zero’ signals climate ambition and holds the promise of strong action. Countries and companies alike are taking the pledge to become net zero as early as 2030, and by 2050 at the latest, in line with the Paris Agreement. France, New Zealand and the UK, for example, along with 20 other countries, now have legally binding net-zero targets, as do some of the biggest corporations in the world, including Amazon and Walmart.

Investors are setting their own goals too. Through the UN-backed Net Zero Asset Owner Alliance, 35 of the world’s largest asset owners, with $5.6 trillion in AUM, have pledged to become net zero by 2050, including investors such as Aviva and CalPERS. This has led to greater government and investor pressure for more companies to take serious climate action. Notably, in his 2021 letter to CEOs, Blackrock’s CEO and Chairman Larry Fink called for more business leaders to adopt net-zero targets, or risk being left behind. But how can investors distinguish between companies with a genuine commitment to reducing emissions and those that have set targets with no clear pathway to back it up?

What does ‘net zero’ really mean?

The IPCC defines ‘net zero’ as that point at which “anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere are balanced by anthropogenic removals over a specified period”. Reaching this point by 2050 is critical to limiting global warming, but not sufficient. The ‘net’ in ‘net zero’ has also been slightly misleading; not only does Paris Agreement require us to reduce emissions but also balance them too. To reach 1.5 degrees, global emissions need to have halved by 2030 at the latest and then continue to decrease thereafter. So how does all of this translate into company targets?

How do net-zero commitments differ?

There is currently no standardised approach to setting net-zero targets. As a result, companies approach net zero in inconsistent ways, making it difficult to assess whether a company’s target is contributing positively to the global net-zero goal. There are three key ways (shown below) in which targets differ. Taken together, they can provide insight into how ambitious a company’s target is. Differences include:

where the boundary of emissions is set;

whether a clear pathway of action is demonstrated; and

the extent of reliance on carbon offsetting.

Boundary

First, companies must address emissions throughout their business and supply chains. Scope 3 emissions represent a significant proportion, if not the majority, of emissions for most corporations, particularly in the food and agriculture sector. However, many companies are failing to address Scope 3 emissions in their net-zero targets. Climate Action 100+ released its new Net Zero Benchmark earlier this year and shows that of the 159 companies covered, only 83 (roughly half) had set net-zero targets. Of those, more than half had not accounted for Scope 3 emissions.

Pathway of Action

Second, commitments must be backed up with a clear pathway of action that includes short- and mid-term goals along with actions that the company plans to take to reach them. Nestle’s net-zero roadmap is a good example of the level of information needed. The roadmap includes science-based targets for Scope 1, 2 and 3 to reduce emissions by 50% by 2030, in line with a 1.5-degree warming scenario. Further, they outline the expected emissions reductions resulting from each action, while also considering forecasted business growth. For example, Nestle plans to reduce CO2 emissions from their dairy and livestock supply chain by 21.3 million tonnes by 2030, 8.4 million tonnes of which will come from improving farm productivity. Whilst this plan is not perfect, the company’s approach along with its disclosure of key milestones allows investors and civil society to hold the company to account and call out elements of the strategy that raise questions or concerns.

Offsetting

If a company has not proposed a significant reduction in emissions or set science-based targets, it is likely that it will use carbon offsetting to achieve net zero.

Carbon offsetting refers to the process of reducing emissions in one area to account for emissions produced elsewhere. This can range from planting trees to investing in renewable energy. However, the capacity for reforestation has been greatly over-estimated given that land available for tree planting is finite. Shell recently announced its plan to achieve net-zero by 2050, which includes “planting forests the size of Spain” (or 50 million hectares), while continuing to grow the production of natural gas and oil. This equates to roughly 10% of the world’s available land for forest planting, using the UN’s estimate.

This is not sustainable.

Given the limited capacity for reforestation, the current cost of carbon capture and other carbon removal technology, these methods should be reserved as a last resort for the emissions that are hardest to avoid.

The October 2018 report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) made it clear that if we are to have any hope of curbing global warming, we need a definitive transition away from our current high-carbon lifestyles: by travelling electric, embracing renewable energy, eating less meat and wasting less food. [12]

Assessing retailers and manufacturers’ net-zero ambitions

The supermarket chain, Morrison’s, recently came under scrutiny after announcing its commitment to be supplied wholly by ‘net zero’ British farms by 2030; and reach net zero without reducing the amount of meat it sells. Agricultural experts are sceptical about the feasibility of the company’s goal, given that meat production is one of the hardest sectors to decarbonise. Beef, for example, accounts for 45% of the company’s emissions, yet only 5% of products sold.[13]

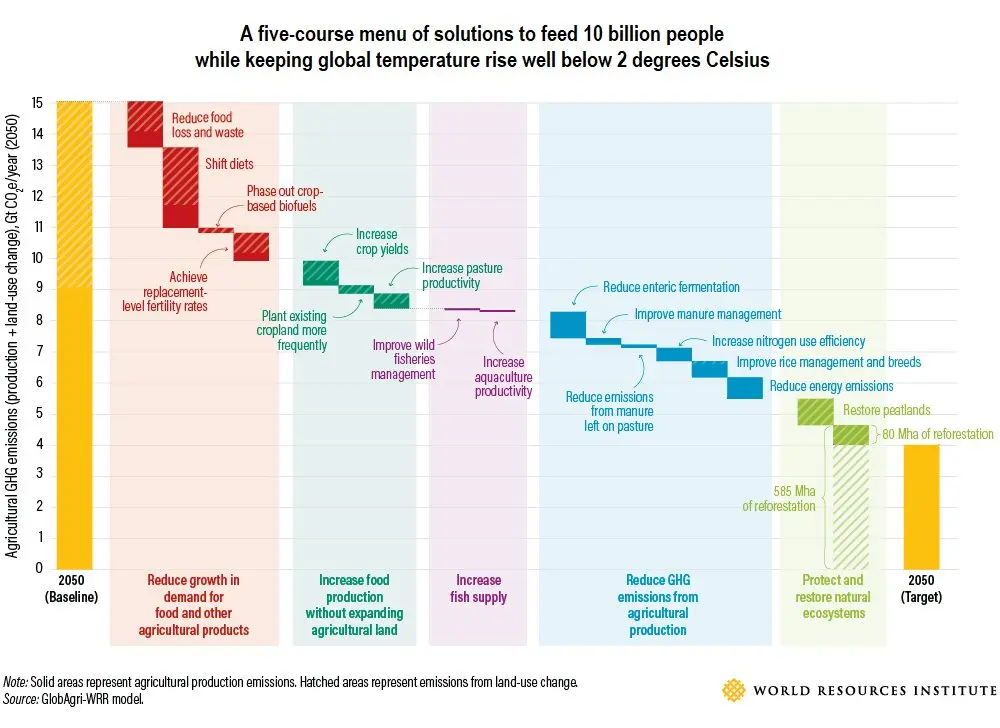

Without offsetting, food retailers and manufacturers will be unable to make the necessary carbon reductions unless the sale of animal protein is reduced. As demonstrated in the image below, shifting diets is the single biggest thing we can do to reduce agricultural emissions, and is critical for the industry to reach net zero. Morrison’s net-zero pathway, which relies on large amounts of offsetting to balance the expected increase in meat sales, is one that other retailers will not be able to follow.

The dietary transition is already underway. Bill Gates has invested in alt-meat start-ups like Nature’s Fynd and Beyond Meat, stating that “rich countries should move to 100% synthetic beef” to reduce deforestation and avert the climate disaster. Tesco, another UK retailer, and Unilever have announced time-bound targets to increase the share of nutritious plant-based options in their portfolios. Moreover, they are actively engaging their consumers on the environmental benefits of a plant-based diet. Nestle also identifies the shift to alternative proteins as a key mitigation opportunity, equating to 1.5 million tonnes of CO2

If food retailers and manufacturers ignore the need to diversify their product portfolio away from carbon-intensive commodities, such as beef, it will undermine their climate targets and put them at a competitive disadvantage.

For investors, the bottom line is that any food retailer or manufacturer with a net-zero target that fails to addresses the sale of meat and dairy or the reduction of Scope 3 emissions is not going to be a driving force in achieving the 1.5-degree target. Companies need to provide a comprehensive pathway of action, backed up by science-based targets, that will allow them to achieve net zero with minimal offsetting.

FAIRR’s Sustainable Proteins engagement is aimed at doing just that. It asks companies to acknowledge the material impact that animal proteins pose and respond with time-bound strategies to shift their product portfolio towards more sustainable proteins, which includes plant-based and alternative proteins. Phase 5 of the Sustainable Proteins Engagement is now well underway, with a progress report being launched in September 2021.

In the second part of this series, we will look at how protein producers have been adopting net zero and the specific challenges they might face on the road to reaching their goals.

FAIRR insights are written by FAIRR team members and occasionally co-authored with guest contributors. The authors write in their individual capacity and do not necessarily represent the FAIRR view.