Ending hunger, achieving food security, improving nutrition and promoting agricultural practices that are beneficial – rather than detrimental - for the climate and nature, is a mammoth task.

For policymakers and investors alike, decisions addressing risks and impacts in one area can result in negative consequences in another, especially when these goals are approached in silos, rather than holistically.

For example, promoting feed additives can reduce emissions but can negatively impact biodiversity, particularly if it leads to increased intensification of livestock farming, which can result in pollution, and deforestation linked to animal feed supply chains.

In fact, understanding how to balance the many, connected (and sometimes) competing interests and considerations around food, climate and nature is something that world leaders will be grappling with shortly, as the UN Biodiversity COP 16 negotiations continue in Rome later this month.

This Insight piece examines some of the trade-offs that can arise when considering climate and nature goals in the agri-food industry and looks at how policymakers and investors can avoid these and instead create win-wins that contribute to a more sustainable food system.

Intensive livestock production: A false friend for reducing emissions

Farming systems that rely on intensive livestock production may be more efficient in terms of the space, food and time required to rear the animals, thereby reducing the intensity of greenhouse gas emissions, but they create a host of other sustainability risks.

These include detrimental biodiversity impacts caused by increased animal feed demand, pollution and contamination from animal waste, loss in soil quality from reduced grazing and increased use of antibiotics, as explored in FAIRR’s Tackling the Climate-Nature Nexus report.

Furthermore, reducing the GHG emissions intensity of livestock production does not necessarily lead to a reduction in absolute emissions, as highlighted by the IPCC.

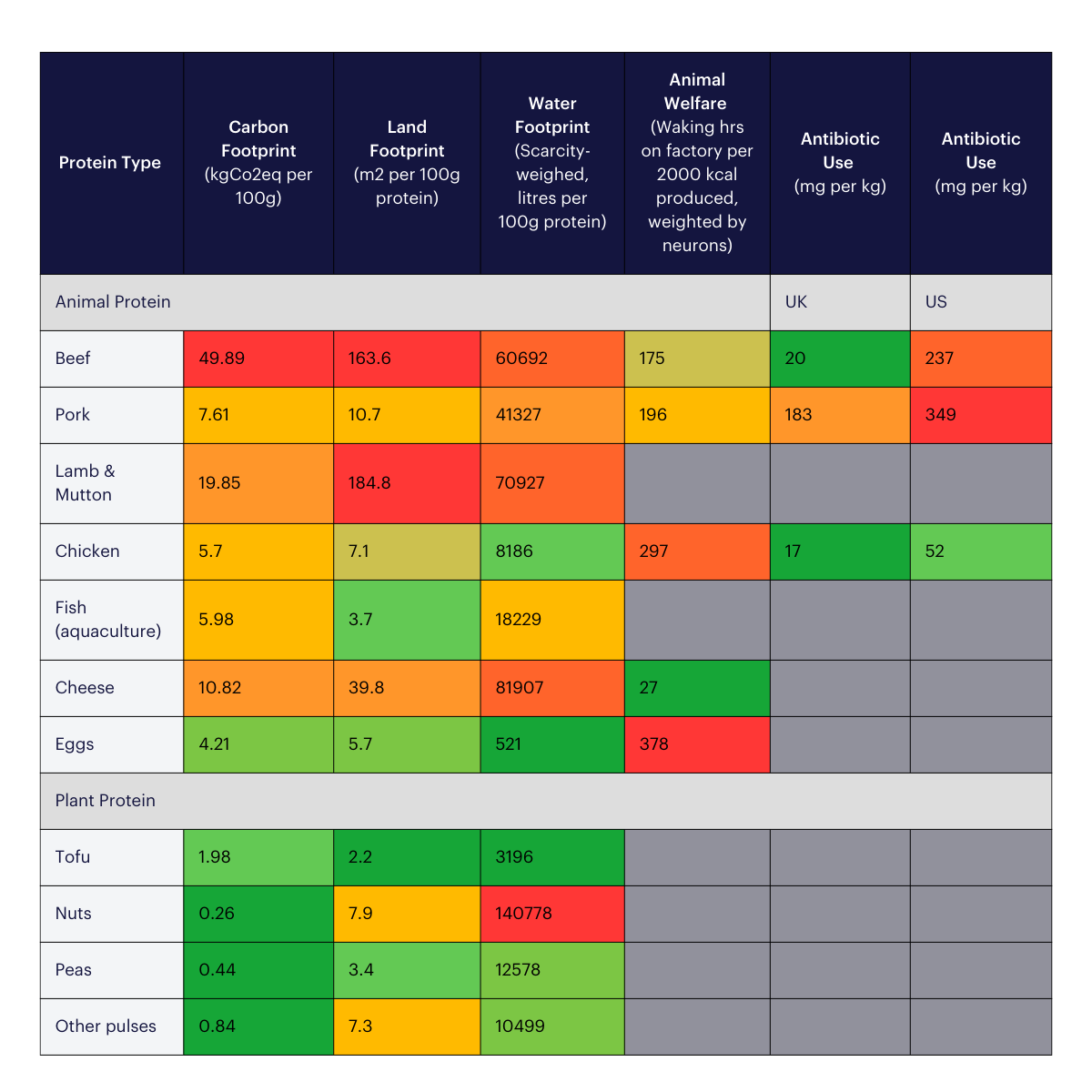

The table below depicts the estimated carbon, land use and water footprints per 100g of various proteins as well as average antibiotic use and hours spent in confined space. While shifting from beef to poultry production creates a lower carbon and land footprint, the associated animal welfare implications are not favourable. This is not a question of ethics, but of material risk, such as the spread of diseases associated with close confinement disrupting supply chains.

Indeed, as highlighted in the 2024 key findings of the Coller-FAIRR Protein Producer Index, animal welfare and antibiotic stewardship are closely linked, with poor husbandry practices contributing to the overuse of antibiotics.

Table 1: Resource footprints, health and antibiotic use implications for different proteins

Sources: Carbon, land and water footprints: Poore,J., Nemecek,T., Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science, 360, 987-992 (2018). https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aaq0216; AMR use: www.saveourantibiotics.org; animal welfare data: Peters, D. et al, (2017, December 4). An Ethical Diet: What are the impacts of our food choices? AARP. https://ethical.diet/

Focusing solely on GHG intensity measures obscures the links between nature and climate, and the mutually reinforcing impacts that can arise between the two.

The material risks associated with intensive livestock production can also expose investor portfolios to significant losses. Farmers operating on degrading land have seen their market value decline by 13%, for example, while antimicrobial resistance caused by the misuse and overuse of antibiotics could cause annual GDP losses ranging from US$1trn – US$3.4trn.

To avoid these trade-offs between climate and nature, policymakers, investors and companies need to consider the multi-faceted implications of the policies, investments and solutions that are available, prioritising those that deliver positive outcomes for climate and nature while solving the challenges that poverty and food insecurity present. But what do these potential win-wins look like?

From trade-offs to opportunities

A key focal point of recent climate negotiations has been the UN Food and Agriculture Organization’s proposed Global Roadmap to 2050 for Food and Agriculture, which has been slated for release over the last two years.

The FAO’s summary document, published at COP28, focused on climate change and food security but did not give nature equal footing with these two goals.

Investors have been calling for a clear roadmap to achieve food security and nature goals by 2050 without breaching the 1.5°C threshold since 2022, backed by Ban Ki Moon, Mary Robinson, Christiana Figueres, and the Net-Zero Asset Owners Alliance.

If it is fit for purpose and encourages countries to make the most of climate adaptation and mitigation strategies that support multiple goals, it has the potential to provide a win-win.

As the IPCC highlighted in its Sixth Assessment Report, many actions used to mitigate emissions in food systems also increase their resilience, such as improving cropland management and better biodiversity management.

Agroforestry, which integrates trees and shrubs into farming systems, can contribute to emissions reductions while helping farmers to increase their productivity, while protecting wetlands can buffer against climate extremes like flooding.

Investing in nature-based solutions and regenerative practices could also represent significant investment and revenue-generating opportunities in the future, such as:

private markets investments into farms that need support to adopt regenerative practices; and

green or sustainability-linked bonds, issued by governments and corporations, whose proceeds are allocated to agricultural projects with climate mitigation and adaption goals.

The UN Environment Programme estimates that investment in agroforestry needs to increase from US$56 billion this year to US$87 billion in 2030, for example. FAIRR’s new report on financing climate and nature-based solutions explores the capital flows into nature- and technology-based interventions in livestock farming in more detail.

Protein diversification: reducing sustainability risks and improving food security

Existing climate mitigation efforts are only one lever in the transition to a more sustainable food system, however, and need to be used alongside interventions that encourage more diverse and sustainable diets.

Protein diversification represents a nascent but growing market opportunity, with novel alternative protein sources forecast to account for at least US$290 billion by 2035, according to Boston Consulting Group, while also providing a significant lever to reduce multiple sustainability risks.

Plant-based proteins produce 70 times less greenhouse gas emissions than an equivalent amount of beef and use 150 times less land, according to an analysis by the UK’s National Food Strategy.

Around 40% of global cereal crops are used for animal feed, according to Our World in Data. Diversifying protein production, from plant-based protein to fermentation or cultivated meat, can increase food security and sovereignty, reducing reliance on global supply chains and lowering the risks that arise from zoonotic diseases, tariffs and geopolitical instability.

Some governments are already moving ahead in this area. For example, China recently opened its first alternative protein research and development centre, while the UK government announced last year that would create a “regulatory sandbox” to explore the safety assessments and guidance needed to approve the sale of cultivated meat in the UK.

The future of food depends on win-wins

The world’s food system will only be sustainable if it works in harmony with nature’s ecosystems and services, and these, in turn, can only keep functioning with a resilient climate for all.

Addressing the systemic risks of climate change, nature loss and global hunger requires a cohesive strategy that draws on and takes advantage of the linkages between these issues to solve them, rather than elevating one area to the detriment of others.

Investors can take several crucial actions here, such as engaging with portfolio companies to reduce the material sustainability risks linked with doing business-as-usual and urging policymakers to consider climate and nature trade-offs in agri-food policies and regulations.

FAIRR will continue to facilitate these actions, ultimately enabling investors to deploy capital that provides win-wins for their portfolios and the global food system at large.

FAIRR insights are written by FAIRR team members and occasionally co-authored with guest contributors. The authors write in their individual capacity and do not necessarily represent the FAIRR view.