Earlier this year, farmers across the world protested growing economic strain on agri-food producers. Many of the protests centred around increased competition from imports, low-profit margins, subsidy cuts, and environmental policies.

Amidst the farmer protests, proponents of intensive livestock production pointed to meat alternatives as a threat to farmer livelihoods. However, alternatives only make up 2% of the animal protein market, and certain types, like cultivated meat, have not yet been approved in Europe, where the bulk of protests took place. Further, alternative proteins are relatively new to the market whereas farmers’ economic struggles have been deepening for decades.

Over the last century, global protein production has shifted from small-scale farming to highly industrialised production systems to increase the availability and affordability of meat and dairy products. For instance, the total number of farms in the EU decreased by 5.3 million between 2005 and 2020, with 87% of these closures being small farms on less than 5 hectares. Despite this decline, the amount of land used for farming remained largely unchanged, reflecting growth in the number of larger farms. Recent analysis from Bryant Research suggests that the rise in intensive farming has coincided with a decline in farming jobs. Centralised and intensive production systems concentrate farmer ownership into the hands of a few large-scale producers, decreasing the feasibility of small-scale farming.

Subsidies centred on large-scale farms

FAIRR identifies that the distribution of agricultural subsidies may also contribute to the challenges small-scale farmers face. For instance, under the European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), direct payments are allocated in accordance with farm size, and as a result, 80% of these payments go to 20% of farmers, who are typically large-scale and industrialised.

Additionally, more than 80% of CAP subsidies go to animal production or feed, despite the associated adverse environmental outcomes and their burden on the wider economy. For example, in 2019 Brazil’s beef industry (including retail and associated sectors) was linked to 90% of deforestation in the Amazon, which in turn caused domestic losses of over US$285 billion, equivalent to 15% of the country’s GDP that year.

How do we feed a growing population while benefiting farmers and the environment?

With the global population expected to reach 8.5 billion by 2030, an 8% increase from 2020, and with incomes on the rise, animal protein production is projected to grow by 14% in the same period. The growing demand for protein would allow for alternative protein products to grow without replacing animal protein sources, and can provide a diversified income for farmers. However, to prevent the environmental and social impacts of industrial animal agriculture from escalating further, a growing body of scientific consensus recommends that production and consumption patterns need to (A) be more sustainable and (B) diversify protein sources. Both approaches have deep implications for animal supply chains.

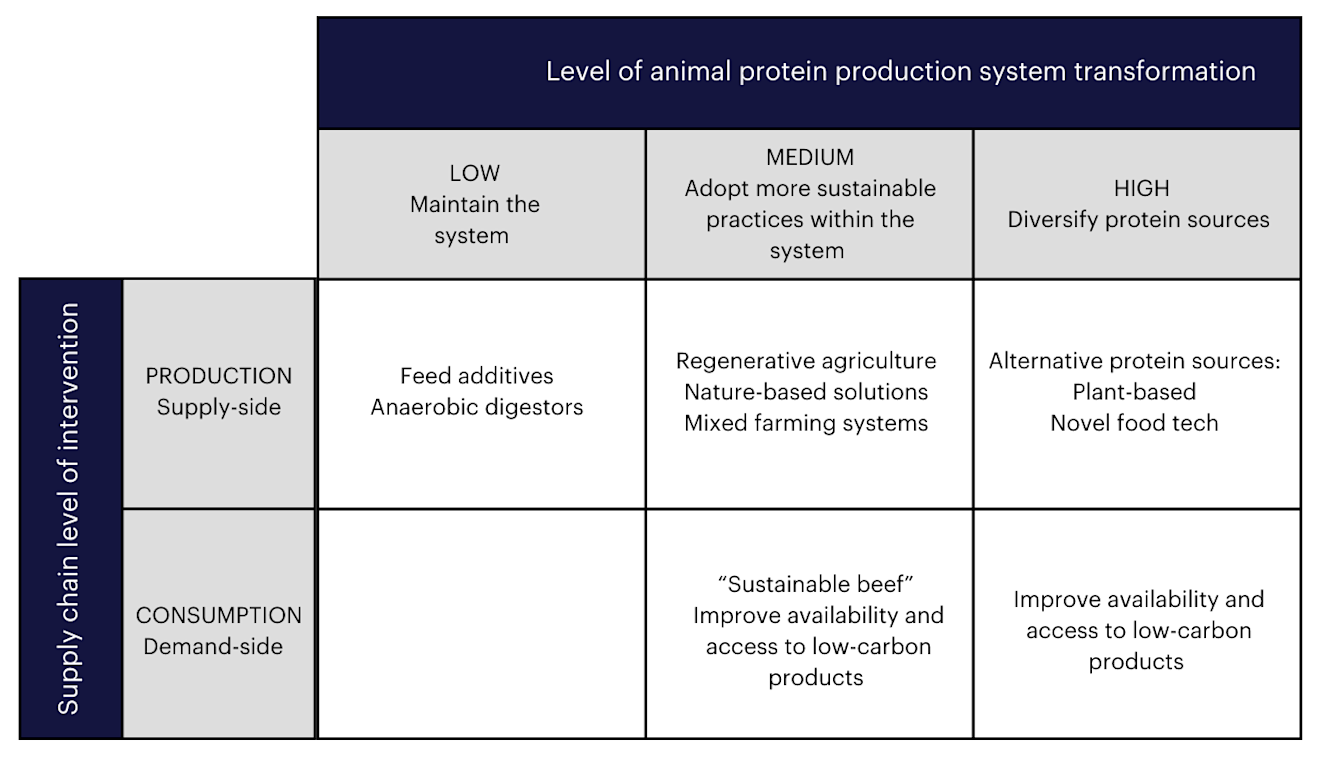

Regenerative agriculture has gained considerable traction within the agri-food sector as a way of reducing the environmental and social harm associated with conventional production practices, but on its own cannot fix our food system. The transformation to a sustainable food system requires a combination of levers throughout the supply chain (Table 1) deploying production/supply-side interventions alongside consumption/ demand-side interventions, such as a diet shift to reduce overconsumption of animal products in favour of plant-based protein. Hence, it is likely that regenerative agriculture will be part of a dual approach to food system transformation which addresses existing production and consumption patterns in order to deliver meaningful change.

Table 1: Approaches to reducing emissions in agri-food system (high-level analysis not comprehensive)

Source: FAIRR 2024

Government support and policy intervention are paramount to succeed in transitioning our food system to more sustainable production and consumption patterns. On the production/supply-side, repurposing agricultural subsidies could address inequalities and enable the sector to sustainably meet growing demand for protein. FAIRR’s G20 investor statement, backed by investors with over US$7 trillion in combined assets, recommends that Finance Ministers repurpose agricultural subsidies, highlighting the importance of increasing the funding available for just transition mechanisms, to support farmers with shifts towards sustainable farming.

In terms of recent developments on this topic, the EU Strategic Dialogue report recommended in September 2024 that a “Just Transition Fund should be established outside the CAP to complement support for the sector’s swift sustainability transition”, and also recommended that the European Investment Bank should implement a specific group loan package for the sector.

In terms of consumption/demand-side interventions, any company or government strategy that supports a diet shift to increase alternative protein consumption must consider the socio-economic implications for animal protein supply chains, and the perspectives of its stakeholders, to support their diversification towards plant-based protein commodities and protein production methods that will benefit from the diet shift e.g. mixed farming systems and novel protein sources.

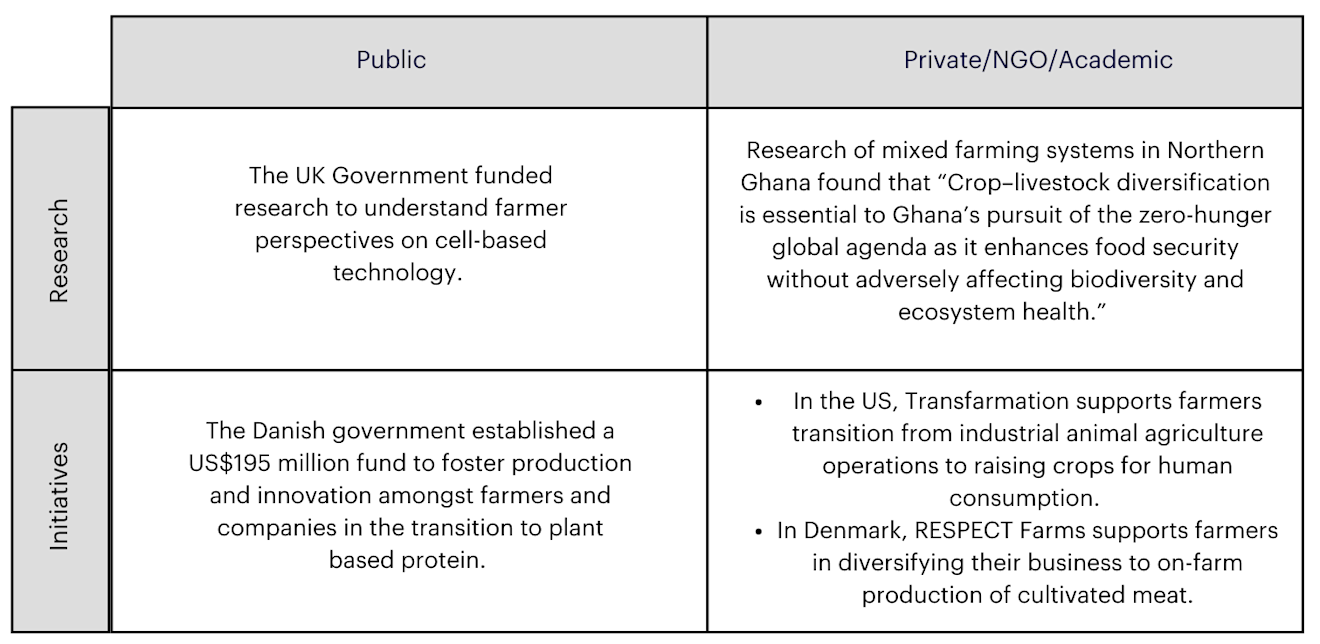

Ensuring that animal farmers benefit from emerging market opportunities, such as sustainable production practices and the growing demand for alternative proteins (Table 2), presents opportunities to alleviate their ongoing economic pressures and accelerate the food system transformation.

Table 2: Examples of public and private initiatives supporting smallholder animal farmers diversify or transition to alternative protein production.

Farmers are the lynchpin of any successful strategy to transition to a more sustainable agri-food system. They are ultimately responsible for adopting and implementing the practices that drive agricultural transformation worldwide. Without their support, even the most comprehensive transition strategy will fail. Transitioning away from established practices towards more sustainable practices and commodities could create a near-term risk for farmers regardless of the long-term benefits. The risk to incomes during a transition is meaningful to every farmer, but particularly to small-scale and indigenous farmers in the Global South. Governments and companies must therefore work closely with farmers and their communities to de-risk the transition and ensure they do not bear the burden of change. Compromises between margins, retail pricing and building long-term resilience in the supply chain may need to be made.

References (Table 2, from right to left):

FAIRR insights are written by FAIRR team members and occasionally co-authored with guest contributors. The authors write in their individual capacity and do not necessarily represent the FAIRR view.