Introduction

The recent outbreak of bird flu spreading through dairy herds in the United States has virologists around the world on edge. Though the Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (H5N1) has been around since 1996, this is the first known instance of it spreading to cattle, between cattle, and from cattle to humans. In its current form, the risk of transmission to and between people is thought to be quite low, but as time goes by, the risk of mutation increases and so does the pandemic potential of this virus.

Last week, two developments further elevated concern. First, the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) confirmed that a second person has caught bird flu from dairy cattle.1 Second, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) announced that bird flu virus particles were found in beef tissue for the first time.2

In a related bit of news, last Friday, negotiators on the WHO Pandemic Preparedness Treaty announced that areas of disagreement were too great for there to be any hope of researching resolution in the time allotted to them.3 Instead of arriving at the World Health Assembly in Geneva this week with a draft treaty for leaders to ratified, they have arrived asking for an extension.

Pandemic treaty talks were launched by world leaders in the aftermath of COVID-19 in hopes of establishing systems and policies that reduce the chance of future pandemics and of reduce the damage they cause when they do occur.

COVID-19, a zoonotic disease which spread from wildlife to humans and then across borders with impunity, served as a stark lesson on the need for global pandemic prevention, preparedness and response coordination. Zoonotic diseases spread between people and animals.

Both COVID-19 and the repeated ravages of bird flu on egg and poultry production, make reducing risk of zoonotic spillover to livestock and humans a top priority to be addressed in the treaty.

Two-and-a-half years in, and negotiators have so far been unable to gather enough international support for provisions designed to prevent outbreaks such as the one raging through dairy cattle in the US right now. With 75% of all emerging infectious diseases zoonotic in origin, this is a critical area in need of resolution. Many of the 70 billion animals reared for food globally are raised in conditions that make for the easy and rapid spread of zoonotic disease. Fortunately, through increased surveillance, on-farm changes and other measures, these risks to and from the animal agriculture sector can be significantly reduced.

The current bird flu outbreak in dairy cattle in the US serves as a critical reminder of the need for a robust global pandemic treaty complete with concrete commitments aimed to reduce risk of zoonotic diseases spreading to humans. Such a treaty is needed for obvious global health reasons, but also financial ones. Outbreaks of zoonotic disease in animal agriculture present significant material and systemic risk to investors.

In Geneva this week, governments should re-double efforts to arrive at a robust WHO Pandemic Preparedness Treaty that reduces the risks of further pandemics of animal origin. Doing so, will save lives and help safeguard economic stability and financial returns.

Bird flu in cows

Bird flu in cattle was first discovered in Texas US on 4 March 2024, however various analyses indicate that the virus likely first jumped to dairy cattle in late 2023.4 Fast forward to May 2024, and the disease has been detected in over 60 herds across nine US states,5 with studies of both milk products and wastewater indicating that the virus is likely far more widespread than the number of confirmed cases would indicate.6 A new study shows that of the dozens of times the virus has mutated so far, some are making it more adept at spreading to humans, though risk remains low.7 Scientists are closely tracking on-going mutations. As a precaution, over half of the US stockpile of H5N1 flu vaccines is being mobilized for deployment if and as needed.8

High viral loads are found in raw milk from infected cows, including that from asymptomatic cows. The US Food & Drug Administration (FDA), health experts and the CDC recommend against consumption of raw milk and products that contain raw milk.9 The FDA and the USDA have indicated, based on the information currently available, that the commercial milk supply in the US is safe as a result of pasteurization and of the diversion and destruction of milk from sick cows.10 USDA testing suggests that bird flu is not viable in properly cooked ground beef.11

Whilst cattle who are infected are recovering from the disease, and the two farm workers known to have caught bird flu from dairy cows suffered only minor symptoms. A great deal is unknown about how the disease is spreading, how widespread it is and how much risk there is of mutation into a variant with more serious health consequences for cattle, humans, and other animals.

Surveillance efforts were slow at the start, resulting in missed containment opportunities. Despite recent increases, experts argue too few dairy cows and farmworkers are being tested.12 While the virus is low risk to humans in its current form, there is concern that mutations may change that. Until the bird flu virus in cattle is contained, this outbreak remains a potential risk to humans.

Risk to capital of zoonotic disease outbreak

Zoonotic disease outbreaks in intensive animal agriculture systems present significant material risk to investments. There are costs, uncertainties and supply disruptions associated with disease sickening and killing livestock, and the culling of animals to prevent the spread of disease.

Investors in downstream firms that produce and sell products containing animal proteins also face material risk as a result of supply chain disruptions and increased input prices. Depending on the severity of the outbreak, the same can be true for investors in upstream firms that provide supplies (such as feed and medicines) and services to protein producers.

The more significant the outbreak, the greater the potential risk of knock-on impacts to investments in a wide range of industries. Both the material and systemic risks to capital increase in cases of human-to-human transmission of zoonotic diseases, as evidenced by the economy-wide impacts experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The current outbreak of bird flu in dairy cows, like many outbreaks, is creating uncertainty for investors. Cattle futures fell sharply in late April following reports that the USDA would be requiring bird flu testing on dairy cattle transported between states.13 Cattle futures have since recovered.14 Colombia has put restrictions in place on imports of beef from the United States, but is so far, the only nation to have done so. The government has not called for the culling of dairy cows.

To date, there have been no reports of notable shifts in sales or prices of beef, pasteurized milk or other dairy products containing pasteurized milk.15

Only a few months in, future trajectories of the outbreak and its impacts are impossible to guess. The low market and financial impacts of the bird flu outbreak in dairy cows experienced so far stands in sharp contrast to the economic impacts of outbreaks of bird flu in poultry in the US and Europe in recent years.

In the US, attempts to contain the spread of bird flu in poultry led to over 90 million chicken and turkeys being culled since 2022.16 Mass culling of poultry on a global scale due to bird flu exacerbated global food price inflation and products, including eggs and chicken ready meals, saw price increases following the 2022-2023 outbreak. In December 2022, lower-than-usual US shell egg inventories, combined with increased demand, resulted in several successive weeks of record high egg prices. The average shell-egg price was 267% higher during the week leading up to Christmas than at the beginning of the year and 210% higher than the same time a year earlier.17

Moreover, disruptions in production cycles and uncertainties about future capacity present potential financial risks for protein producers and the broader food supply chain. These issues could significantly impact some of the world’s largest poultry producers.

In addition to the high costs borne by producers, governments and customers, each outbreak of bird flu in commercial laying hen and broiler chicken populations – and now in dairy cows – brings with it risk of pathogens mutating and resulting in human-to-human transmission. With it increasing the potential financial and material implications of this significant18 systemic risk to investors.

FAIRR’s Emerging Disease Risk Ranking

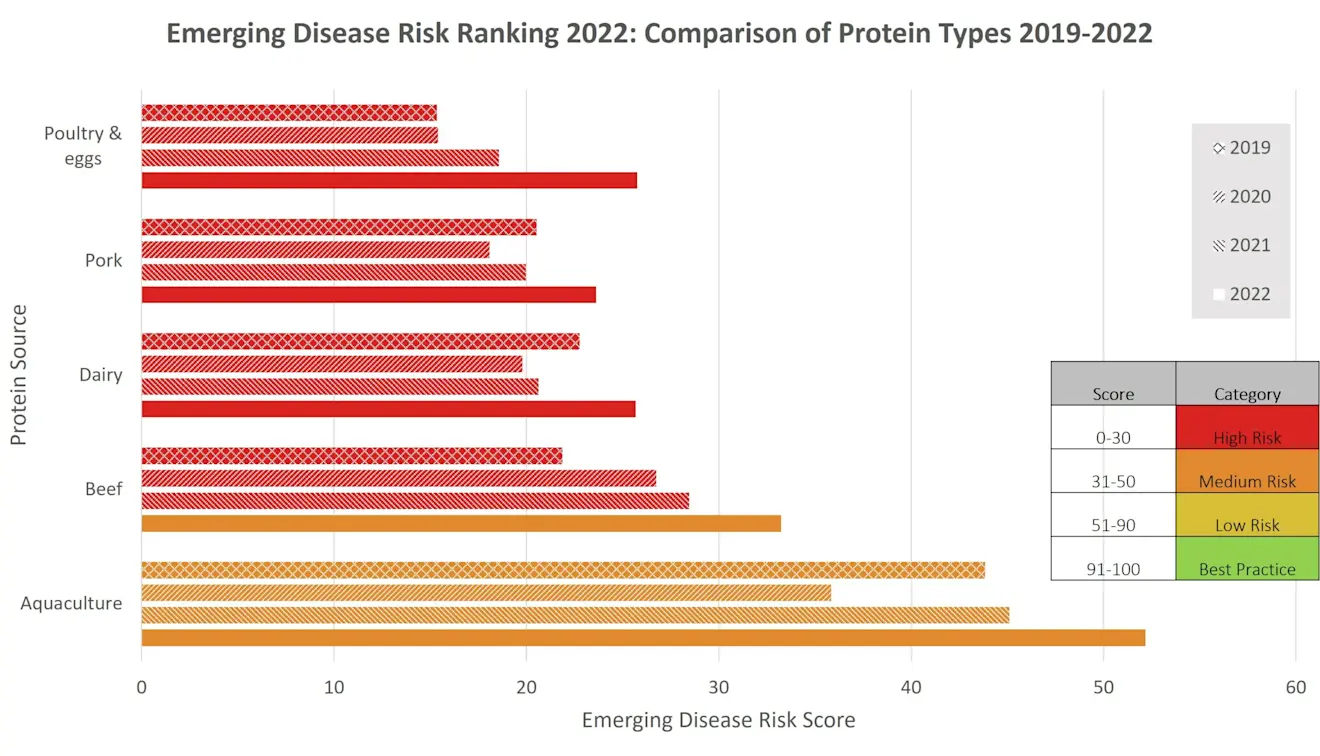

FAIRR has adapted data used in the Coller FAIRR Protein Producer Index to create an Emerging Disease Risk Ranking. The Emerging Disease Risk Ranking has been determined by evaluating the 60 companies in the Index across five categories of animal protein – poultry & eggs, pork, dairy, beef, and aquaculture - on six risk indicators: deforestation & biodiversity loss, antibiotics, waste, and pollution, working conditions, food safety and animal welfare, as illustrated in Figure 1.

The data shows improvement across all protein classes between 2019 and 2022. Despite steps in the right direction, all the animal protein classes, except for aquaculture, were found to present medium to high pandemic risk. Even the aquaculture sector, with its score of 53, has considerable distance to go before achieving a “best practice” rating (91-100). This suggests that the animal protein industry has yet to adapt sufficiently to the emerging disease risks posed by industrial practices.

Figure 1: Emerging Disease Risk Ranking 2022: Comparison of Protein Types 2019-2022

What is One Health?

Policy makers and health experts continue to call for a coordinated One Health approach to address drivers of disease risk. One Health highlights the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health in efforts to address the root cause of disease transmission. This call is particularly pertinent as member states from around the world enter the concluding stages of negotiations of the World Health Organization (WHO) Pandemic Preparedness Treaty.

The Pandemic Preparedness Treaty

As mentioned above, in 2021, in the immediate aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, talks were launched, led by the WHO to develop a new global treaty on pandemic preparedness and response.

Concerns have grown in recent months that after two-and-a-half years of negotiation, the treaty was not on track to deliver on its promise. Much of what needs to be done to reduce pandemic risk, including as relates to zoonotic disease control measures in the animal farming sector, is known. Despite this, converting the knowledge to concrete provisions and consensus has proven difficult across the years.

Though the negotiators failed to get a draft agreement in place within the time span allocated to them, indications are strong that the effort will not be abandoned. WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus has expressed confidence that with time a deal will be reached. This week in Geneva discussions are underway about how much of an extension to give to the negotiators.19

Negotiations around One Health provisions reportedly were a sticking point straight through last week.20 Another area on which consensus could not be reached before the clock ran down was the matter of “timely and reliable sharing of pathogen samples and genetic sequence information, along with equitable sharing of benefits arising from their utilization”.21

If the treaty is to deliver on its original ambition, it will need to contain stronger commitments reduction of zoonotic risk and the provision of more equitable access to pandemic-related products. Pandemics spread across species and across borders. Efforts to prevent and contain them must, too. From a FAIRR perspective, relating to animal agriculture, we would like to see the following outcomes from the WHO Pandemic Preparedness Treaty including:

Clear and enforceable obligations to prevent zoonotic disease outbreak - without which risk of future pandemics originating from animals remains high; and

The prioritisation and commitment to implement One Health principles, which highlight the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health in efforts to address the root cause of disease transmission.

Ensuring these two components will be crucial in enhancing global pandemic preparedness and response efforts, particularly in the face of increasing threat of zoonotic disease.

Conclusion

Global animal pandemics create significant systemic and material risk for investors. They also present a constant spillover risk, where diseases spread from animals to humans and then between humans, leading to a pandemic. As the current outbreak of bird flu in cattle in the US makes painfully clear, we are not yet prepared at either national nor international levels to identify and limit risk of spillover from livestock to humans. Commitments by individual governments to put into place policies that reduce the risk of zoonotic disease spreading through farm animal populations and from farm animals to humans will decrease risk to global health, to financial markets and to return on investment. Commitments by WHO member nations to strengthen and ratify the WHO Pandemic Preparedness Treaty have the potential to bring about the same benefits. The costs in financial terms, and in terms of lost animal and human life, of failing to act preventatively is far too high. The steps needed to reduce risk are known. It is key that leaders act to advert preventable suffering and loss.

References

[1] Economist, “A second human case of bird flu is raising alarm,” 24 May 2024.

[2] https://www.cbsnews.com/news/bird-flu-detected-beef-tissue-first-time-h5n1/

[4] https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/bird-flu-virus-has-been-spreading-in-u-s-cows-for-months/

[5] https://www.cdc.gov/flu/avianflu/mammals.htm

[7] https://www.nytimes.com/article/bird-flu-cattle-human.html

[8] Economist, “A second human case..,” 24 May 2024.

[9] https://www.wkbn.com/news/national-world/bird-flu-why-health-experts-are-so-worried-about-raw-milk/

[12] https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2024/04/25/bird-flu-cows-government-response/

[14] https://www.thecattlesite.com/news/cattle-futures-continue-to-rally-cme

[15] https://www.dairyherd.com/markets/milk-prices/how-much-impact-has-avian-flu-had-dairy-prices

[17] https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/chart-gallery/gallery/chart-detail/?chartId=105576

[18] https://www.fairr.org/resources/reports/industry-reinfected-avian-flu

[20] https://healthpolicy-watch.news/the-pandemic-agreement-why-what-has-been-achieved-so-far-matters/

[21] Ibid.

FAIRR insights are written by FAIRR team members and occasionally co-authored with guest contributors. The authors write in their individual capacity and do not necessarily represent the FAIRR view.