In the coming weeks, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) will release the latest instalment of the 2050 Roadmap for the agri-food sector, aiming to achieve Sustainable Development Goal 2 (eliminating hunger globally) without breaching the 1.5C climate change threshold. This 2050 Roadmap report will be updated by the FAO periodically over the course of the next 18 months, with the full Roadmap report scheduled to be finalised by Nov 2025 in time for COP30 in Brazil. In December 2023, at COP28 in Dubai, the FAO issued a document it referred to as the Roadmap In-Brief, which summarised key themes of this 2050 Roadmap.

FAIRR’s members, like much of the world, are eagerly awaiting the release of this critical report, for the simple reason that is not possible to achieve 1.5C – or anything close to 1.5C – without movement toward lower-carbon agricultural and food production. Feeding the world’s growing population in a way that aligns with global commitments to the Paris Agreement and keeps within planetary boundaries is critical. The mandate is clear. How to achieve it, and the role of policymakers, corporates and investors is less clear.

In face of this critical gap, in 2022, a FAIRR-led coalition of 58 investors with $18 trillion in combined assets signed an investor statement calling on the FAO to develop a roadmap to lay out a pathway that could be used around the world to help operationalize the necessary agricultural and food sector transformation. Ban Ki Moon, former UN Secretary General and one of the architects of the Paris Agreement, joined in the call for the UN-FAO to develop such a roadmap by endorsing the investor letter organised by FAIRR.

In the statement, the signatories explained why such a Roadmap is so important to investors:

In the statement, the signatories explained why such a Roadmap is so important to investors:

“As investors, we recognise the financially material risks to which the food system is exposed, from climate change, biodiversity loss, malnutrition, and antimicrobial resistance, as well as the material impacts that food system activities have on the environment. Accordingly, we urge the FAO to produce a global roadmap to 2050 that mitigates these risks and sets a standard for the industry. It is crucial that this roadmap aligns with the Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting global warming to 1.5˚C while ensuring the protection and restoration of nature, and achieving food and nutrition security goals.”

The direction of travel signalled in a strong Roadmap will give confidence to investors to mobilise capital, align portfolios, engage with companies, and pursue long-term strategies necessary to enable the transition to a sustainable global food system.

Components welcomed by FAIRR from the Roadmap In-Brief

The Roadmap In-Brief, released at COP28, outlines the 10 domains critical to meeting the dual roadmap objectives for eliminating hunger globally without breaching the 1.5C climate change threshold. The inclusion of quantitative milestones and targets that are measurable and time-bound in each of the 10 domains is an important first step on which more will need to be built in the coming years.

Reference in the Roadmap In-Brief to the importance of increased alignment of agricultural subsidies with sustainable development goals is a welcome addition as nearly $470 billion in annual agricultural subsidies, or 87% of the worldwide total, are price distorting and environmentally and socially harmful. In the World Bank’s Detox Development: Repurposing Environmentally Harmful Subsidies report, it notes that agriculture subsidies are responsible for 14% of global deforestation each year. Not only have FAIRR investors and the World Bank calling for agricultural subsidies to align with planetary boundaries, but in the COP28 UAE Leaders Declaration on Sustainable Agriculture, Resilient Food Systems and Climate Action, 159 countries have declared their intention to strengthen their efforts to revisiting or orienting policies and public support by 2025 in ways that reduce GHG emissions, food loss and waste, and ecosystem loss and degradation.

Similarly, emphasis on the need for a just transition in global food systems to support farmers and reduce inequalities was greatly appreciated, and timely, considering the ongoing farmer protests in Europe and vulnerable populations in the global south whose homes and livelihoods are disproportionately affected by climate change. In August 2023, FAIRR investor members with $7tr in combined assets called on G20 nations to increase funding for workers impacted by reforms to ensure a just transition. Shifting current financial incentives away from the production of climate- and nature-damaging agricultural product is an essential part of this transition, with clear material financial risk to investment portfolios if these sorts of shifts are not achieved.

Areas of concern from the Roadmap In-Brief

The problematic role of livestock intensification

The Roadmap Report In-Brief identifies “efficiency of production” as key to achieving the roadmap’s goals on climate and hunger – an element that has been welcomed by trade groups representing the interests of large conglomerates and corporate animal protein and dairy companies. Various organizations and scholars – as noted in this United Nations Environmental Programme summary document and this March 2024 Nature Food paper -- have voiced concern about the compatibility of increased efficiency and intensified production with meeting climate goals in ways that are sustainable.

The Roadmap In-Brief includes the target to increase total factor productivity for livestock by 1.73% every year by 2050. Such increases in livestock productivity not only impacts climate, but also have detrimental impacts on nature and present other systemic risks - including increased antimicrobial resistance – which are insufficiently explored in Roadmap In-Brief.

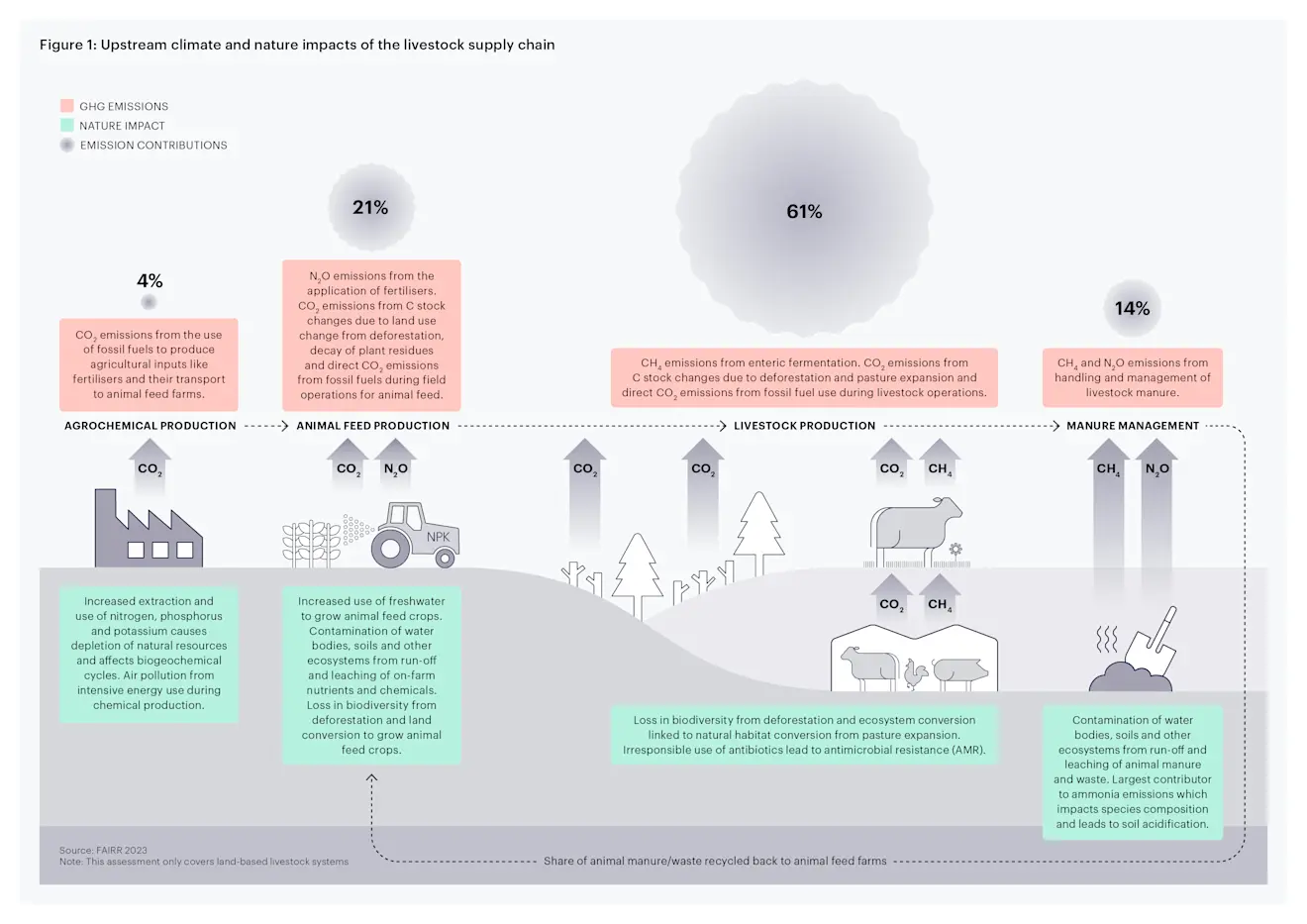

Intensive livestock production is known to have negative impacts on climate and nature (see Figure 1, from FAIRR’s Climate Solutions Report). It is essential that future updates of the UN-FAO Roadmap compare the financial risks and opportunities of different strategies for achieving the Roadmap’s objectives within planetary boundaries, whilst minimising increased negative externalities with biodiversity, human health, animal welfare and other consequences. In short, to succeed, the Roadmap must avoid a narrow focus on greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Some productivity enhancements – such as increasing outputs e.g. litres of milk per cow or per unit of land – can create heightened risks for nature and increase the risk of zoonotic disease or AMR. Therefore, those trade-offs need to be considered.

Investors are concerned about risks to their livestock production investments across the board. Climate is a major concern, but it cannot be addressed in a vacuum, otherwise, we risk the exacerbation of other equally serious systemic risks, including nature and health risks. Investors need more clarity from the UN-FAO on how and where sustainable intensification should be promoted without heightening other material risks.

Figure 1: Upstream climate and nature impacts of the livestock supply chain

Diversification of protein sources

Addressing greenhouse gas emissions and ensuring equitable access to sufficient, nutritious food are the guiding ‘North Stars’ of the FAO roadmap, and investors will expect clarity over the role that diets play in achieving these goals – whilst also being cognisant of wider risks to portfolios associated with current intensive systems of food production, particularly livestock. Such clarity is important because while enabling healthy diets for all is listed as one of the 10 domains of action in the Roadmap In-Brief, there are no milestones regarding shifting away from emissions-intensive diets.

Livestock production uses 77% of all agricultural land – for pasture for grazing and land to grow crops for animal feed. Yet, livestock only produces 18% of the world’s calories and 37% of total protein. The overconsumption of animal proteins in high-income countries disproportionately contributes to climate change, degrades natural ecosystems, and is linked to increased incidences of non-communicable diseases (NCDs). With a growing global population there is a need to transition away from excess animal protein consumption if we are to feed the planet sustainably in a resource-constrained world.

One widely-acclaimed approach, The Eat Lancet’s “Planetary Health Diet”, proposes that animal protein intake should be limited to 84 grams a day (excluding dairy products) and at least 125 grams of plant-based proteins be consumed daily. For example, in certain regions of South Asia where there is a lack of access to a diverse range of foods increasing meat consumption up to the EAT-Lancet’s recommendations of 84 grams could help populations fulfil their daily nutritional needs. In North America, per capita intake of non-dairy animal protein is over 5 times this target and should be reduced.

While integrating practices such as regenerative agriculture, increasing nutrient efficiency, and improving on-farm energy use have significant climate mitigation potential these efforts alone are insufficient. Companies, investors, and governments will play a crucial role in accelerating and maximising the adoption of diverse protein sources that support healthy and sustainable diets – and will welcome guidance in these efforts from the FAO roadmap.

Falling short on biodiversity

While the Roadmap In-Brief makes some mention of natural assets – namely water, soils, forests, wetlands and species diversity – and while the FAO has indicated that it will expand the amount of attention given to nature in future iterations of the roadmap, the importance of this issue cannot be overstated. Quite simply, it needs to be woven through the fabric of the Roadmap efforts as a key factor in the analysis and recommendations.

Nature is not given enough weight in the milestones taking us to 2050 in the Roadmap In-Brief. Safeguarding all natural assets is not listed as one of the 10 domains of action. Instead, only forests and wetlands appear in the listed domains of action. It is a missed opportunity to not see the widely-agreed Convention on Biodiversity target (30 by 30) listed as one of the key targets in the Global Roadmap Report – given that the global food system is the biggest single driver of biodiversity loss. To foster greater international alignment, all key targets of Global Biodiversity Framework which relate to agriculture could be integrated into the Spring 2024 Roadmap report; namely conserving and restoring degraded ecosystems, reducing nutrient loss, reducing risk from pesticide, protecting species diversity and promoting nature-based solutions.

The two targets in the Roadmap In-Brief which do relate to nature -- achieving zero net-deforestation globally by 2025 and zero gross-deforestation globally by 2035 – falls five years short of the international agreement reached at COP26. In the Glasgow Leaders Declaration on Forest and Land Use launched at COP26, 144 countries already committed to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030, not 2035. The UN-FAO should align with this more ambitious and widely-recognised target.

Over the three-year roadmap process, FAIRR would welcome better evidence to support investment in both supply- and demand-side solutions which not only reduce GHG emissions – but also tackle nature-related risks such as water scarcity, pesticide load, biodiversity loss, AMR risk, and animal welfare risks. FAIRR research has shown that even though more livestock producers are making commitments to supply-side solutions which prioritise nature outcomes, they face substantial challenges in deploying such initiatives. With plant-based proteins producing 70 times less greenhouse gas emissions than an equivalent amount of beef for meeting the protein, calorie and nutrition needs of the world’s population needs consideration, inclusive of alternative proteins.

The UN-FAO has the opportunity to mobilise financing for sustainable agricultural practices by setting a target in future iterations of the 2050 Roadmap on the level of investment needed in nature-based solutions focused on conservation and restoration. This would facilitate the achievement of the internationally-recognised target of restoring 30% of degraded ecosystems by 2030 (Target 2 of the Global Biodiversity Framework).

Safeguarding against disease

The agri-food sector needs a coherent vision for how food and nutrition security and climate goals will be achieved, while reducing human and health risks. Without proper guidelines, livestock productivity increases can worsen risks of the spread of zoonotic disease and of antimicrobial resistance in livestock, aquaculture, wildlife and humans. These risks are discussed in turn, below.

On the one hand, the increased spread of zoonotic disease poses serious health risks – with three out of every four new diseases estimated to be transmissible from animals to humans. The animal production industry can play a critical role in preventing such new transmissible disease strains. Pandemics like swine flu and avian flu have been transmitted directly from livestock to humans – as seen most recently in the USA, where currently there is H5N! bird flu is surging in cattle populations, with confirmed cases of the flu being transmitted cow to cow and - for the first time, from cattle to human. This, along with significant sheading of the virus in raw milk, has been declared a matter of serious concern by the World Health Organization.

An extreme example of intensified production can be found in the newly built, large-scale indoor pig facility in Ezhou, China which has the capacity to house and slaughter 1.2 million swine a year. Professor Dirk Pfeiffer, chair professor of One Health at City University of Hong Kong, is among various experts who have voiced concern about the disease risk involved, noting that “the higher density of animals, the higher risk of infectious pathogen spread and amplification, as well as potential for mutation."

Intensive animal production systems – including those of far smaller scale that found in Ezhou - involve crowded conditions, lowered genetic diversity, live transport, and indoor confinement, all of which create an environment for new strains of diseases to emerge and spread. Furthermore, animal protein companies are often highly-exposed to deforestation, which is linked to the emergence of new zoonotic diseases.

On the other hand, increased antimicrobial resistance, due to overuse of antibiotics in the intensive animal production systems, poses serious health risks to humans and to public health and economic stability, with AMR predicted to cost the global economy $100 trillion by 2050 (O’Neill Report, 2016). Almost 5 million people die globally every year due to the underlying cause of antimicrobial resistance. Unless antibiotic use practices in human and animal settings are addressed, it has been predicted that 10 million annual deaths will be caused AMR by 2050.

Intensive animal production systems are a major driver behind this global public health threat because higher-density aquaculture and higher-density livestock housing systems are often heavily reliant on the routine use of antimicrobials. 73% of antibiotics worldwide are allocated to food animals. Inadequate management of animal waste increases the risk of soil and water contamination by antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

The business case for tackling antimicrobial resistance in livestock production is becoming increasingly clear. It presents not only a sector-specific material risk to the livestock, meat, dairy and seafood industries, but also as noted above, significant systemic risks. Viewing antimicrobial resistance to veterinary products as a major health threat, the European Union for example not only prohibits the use of antimicrobials for growth promotion but also prohibits the routine use of antibiotics in raising food animals.

The significant human health risks of AMR and of zoonotic disease need be factored into discussions in the FAO Roadmap, regarding the viability of various approaches to increasing efficiency of animal protein production if we are to ensure the creation of sustainable agricultural systems.

Looking ahead to future roadmap iterations

Above, FAIRR shared top line reflections from an investor perspective on some of the critical elements in the December 2023 Roadmap In-Brief that need to be addressed. It is hoped that this Spring’s Roadmap Report, coming out in a few weeks will signal intentionality on these important issues and that they will be integrated into deep analysis by Nov 2025. Given the magnitude of the task, its complexities and the importance of getting the analysis and recommendations of the UN-FAO roadmap right, it is welcome to see an iterative process for the 2050 Roadmap, cumulating in Nov 2025:

By Nov 2024, the UN-FAO plans to add additional chapters to the 2050 Roadmap report, namely outlining regional pathways and introducing a financial dimension that will allow policymakers, companies, farmers and investors to prioritise actions.

By Nov 2025, the UN-FAO plans to add additional chapters covering country-level plans and analysis. These will act as important examples of how the agri-food transition can look at country-level. Following on from this, it is critical that national governments develop country-specific actions for aligning their food and agricultural sectors with their Paris Commitments within their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). The NDCs, which are due to be updated by 2025, should point to in-country monitoring and reporting mechanisms to help track progress being made. This may help ensure better results in the 2028 Global Stocktake than was the case in 2023.

While we welcome the regional specificity promised in the forthcoming iterations over the next 18 months, important core substantive work is needed at the top-level – including on deforestation and on methane.

By Nov 2025, FAIRR and its investor members would welcome clearer recommendations in future Roadmap iterations, on how the necessary systemic change in current livestock production systems can be brought about. These changes would reduce the unintended consequences associated with intensification, including eliminating the excessive use and misuse of antibiotics in raising food animals to help extend the effectiveness of antibiotics needed to protect human health.

To deliver on the objectives of the roadmap, it will be critical for the UN-FAO to engage regularly in a robust and open manner with leading academics on the calculations, models and the underlying assumptions at the heart of the Roadmap’s analysis and recommendations. A transparent process with rigorous testing of assumptions in interaction with leading scientists – while at times cumbersome – has long been part of the modus operandi of scientific scholarship for the simple reason that it helps ensure highest quality results. Issues such as those raised by Leiden University are likely to come up from time to time and must -- as part of standard practice – be given fair and appropriate consideration. In some cases, the points may be found to be immaterial, and in others they may present important opportunities to shift thinking and improved outcomes. In all cases, sharing the responses publicly will be helpful.

The FAO’s three-year Roadmap process of iterative examination of the issues seems designed to allow for growth in understanding and re-evaluation in the face of new learnings. Open engagement and transparency have the added benefit of reducing the risk of any inadvertent bias as well reducing the appearance of bias.

FAIRR, our investor members and governments around the world are looking to the FAO to deliver a roadmap by COP30 that achieves the difficult – but unimaginably important task – it has been assigned.

Addressing the points raised above will help ensure that the FAO delivers a Roadmap that works for investors, governments, farmers, and future generations. We look forward to working with the FAO and other stakeholders as the roadmap takes shape over the next two years.

FAIRR insights are written by FAIRR team members and occasionally co-authored with guest contributors. The authors write in their individual capacity and do not necessarily represent the FAIRR view.